1st Author: Amine Beyhom | Professor in Musicology, editor in chief of NEMO‐Online and director of the CERMAA (Centre for Research on Music from Arabian and Akin countries) in Lebanon.

2nd Author: Hamdi Makhlouf | Musician, researcher, lecturer at the University of Tunis ‐ Higher Institute of Music (ISM) and scientific supervisor of the CMAM (Center for Arab and Mediterranean Music) in Sidi Bou Saïd ‐ Tunisia.

Abstract

In 2018 NEMO‐Online published the first author’s article “MAT for the VIAMAP – Maqām Analysis Tools for the Video‐Animated Music Analysis Project” – with detailed explanations about more performing tools for the analysis of, mainly, solo maqām music, be it instrumental or vocal. It was followed by two articles in the same review, the 2019 “The Lost Art of Maqām” and the 2021 “Further Analyses from the VIAMAP” which explored further the maqām repertoire including performances from the maqām mainstream as well as from Syriac (Orthodox), Turkish musicians, and Cante Jondo (Flamenco) performances.

This article deals with Tunisian solo performances from the 1932 Congrès du Caire recordings, mainly improvisations of Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb and°Khmayyis° Tarnān onʿūd °ʿarbī°, in a very limited attempt at analysing a repertoire at a given period of time, here at the beginning of the 1930s. The results confirm previous research: each performance – and each analysis – is unique and, while few characteristics may apply to some – or most – of the performances, the rule remains the existence of substantial differences between different regions, performers and instruments. Furthermore, the results of the analyses of the Tunisian istikhbārāt confirm once again, if still needed today, the frequent disparities between theories and practices of music.

- To cite this article: Beyhom, Amine and Makhlouf, Hamdi, 2021, “A VIAMAP exploration of the Tunisian ṭubūʿ“, CTUPM, [URL: https://ctupm.com/en/a-viamap-exploration-of-the-tunisian-tubu/]

- Download the article (PDF).

Introduction

This article is the continuation of three previous articles1 by the first author concerning the new (video) tools used by the CERMAA team2 for the analysis of maqām performances. Knowing that the notation and scale tools used in maqām analysis are biased as they are based on the ideological premises of Western musicology3, video animated analyses become one alternative manner of analysing maqām and other musics – especially solo performances.

While previous VIAMAP (Video Animated Music Analysis Project) analyses concentrated mainly on more complex performances with numerous modulations and musical or vocal and instrumental techniques, the video analyses proposed in this article concern simpler performances, which develop generally one single ṭabʿ4 scale with few modulations. The fourteen analysed instrumental pieces are taken from the Tunisian repertoire – mainly improvisations – recorded at the 1932 Congrès du Caire. We show that the tools developed in the last few years allow for a thorough analysis of this reduced repertoire and, mostly, that even the “simplest” performances by renowned musicians have much to tell about the music that they tried to represent at this occasion.

Prefatory Remarks

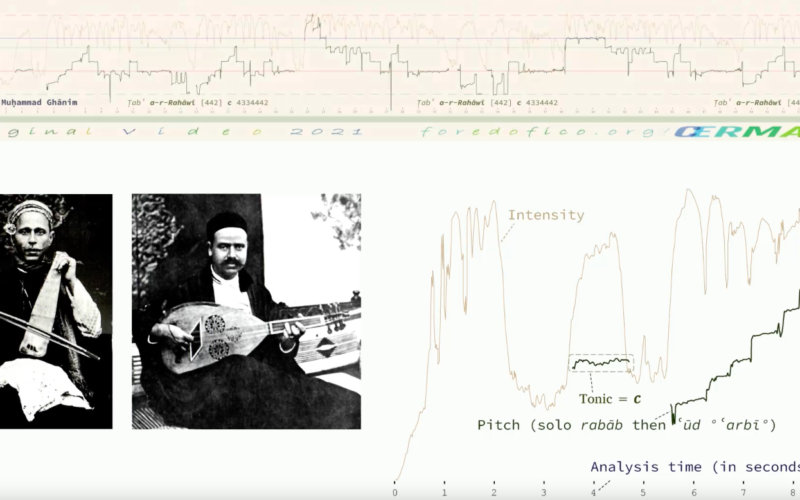

There are seven video analyses5 in all explained in this article, which all concern Tunisian music recorded at the 1932 Congrès du Caire. The seven video analyses concern fourteen istikhbār(s) – taqāsīm6 of the Tunisian tradition (Figure 1). Each video shows the analysis of two successive istikhbār(s) each in a different ṭabʿ (a Tunisian maqām), the first being performed on the r[a]bāb by Muḥammad Ghānim, and the second on the ʿūd °ʿarbī°7 by °Khmayyis° Tarnān.

The videos and ṭ[u]būʿ8 concern, successively:

- Video 1: The ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī9 on rabāb, then ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 50a),10 (link to the video)

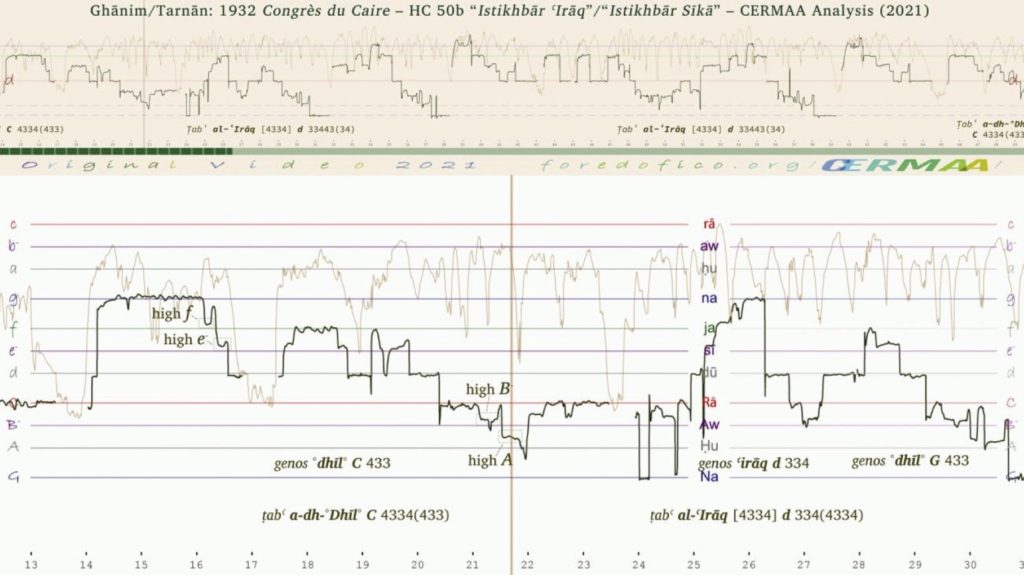

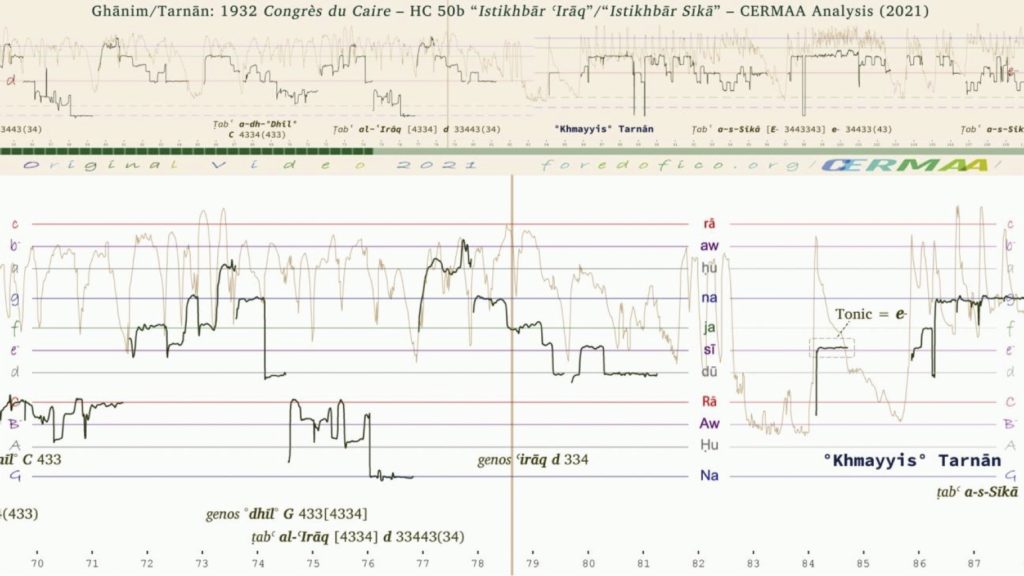

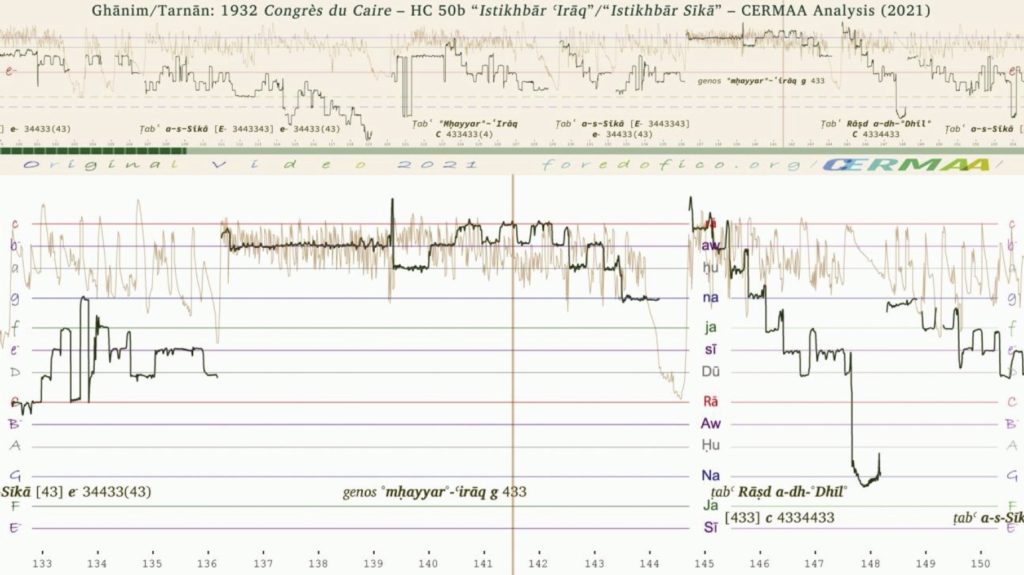

- Video 2: The ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq on rabāb, then ṭabʿ a-s-Sīkā on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 50b), (link to the video)

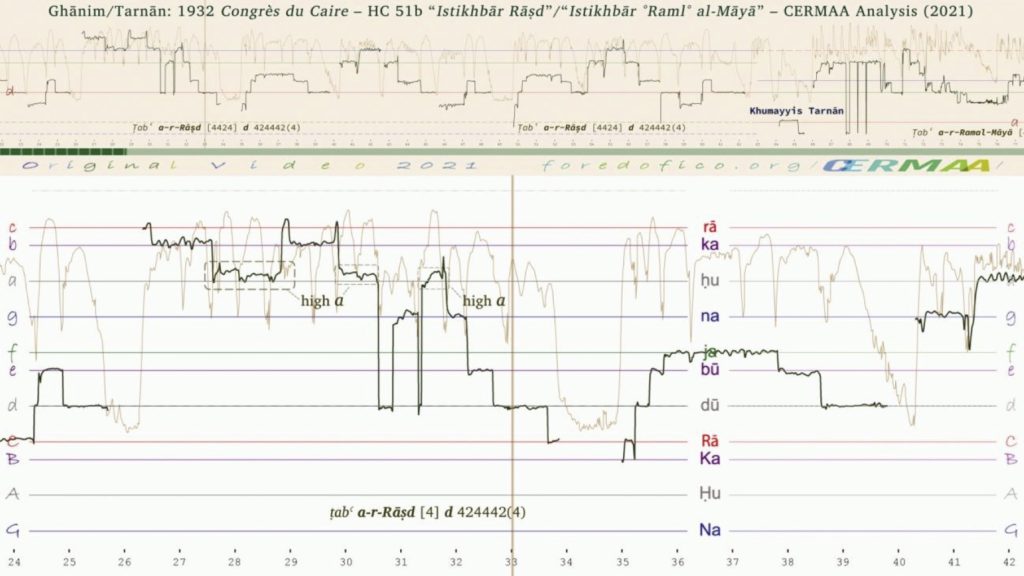

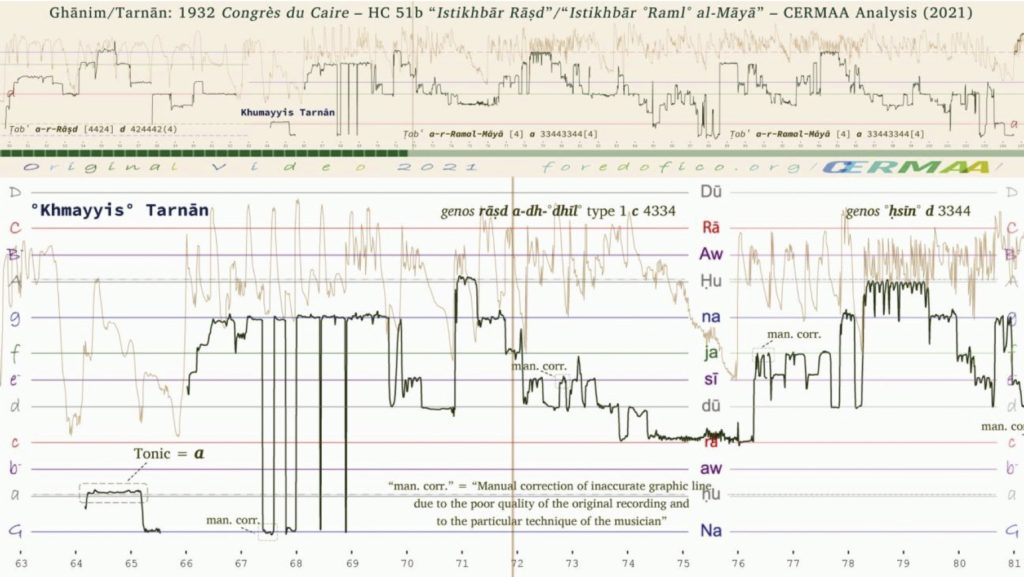

- Video 3: The ṭabʿ a-r-Rāṣd on rabāb, then ṭabʿ °Raml°11 al-Māyā on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 51b), (link to the video)

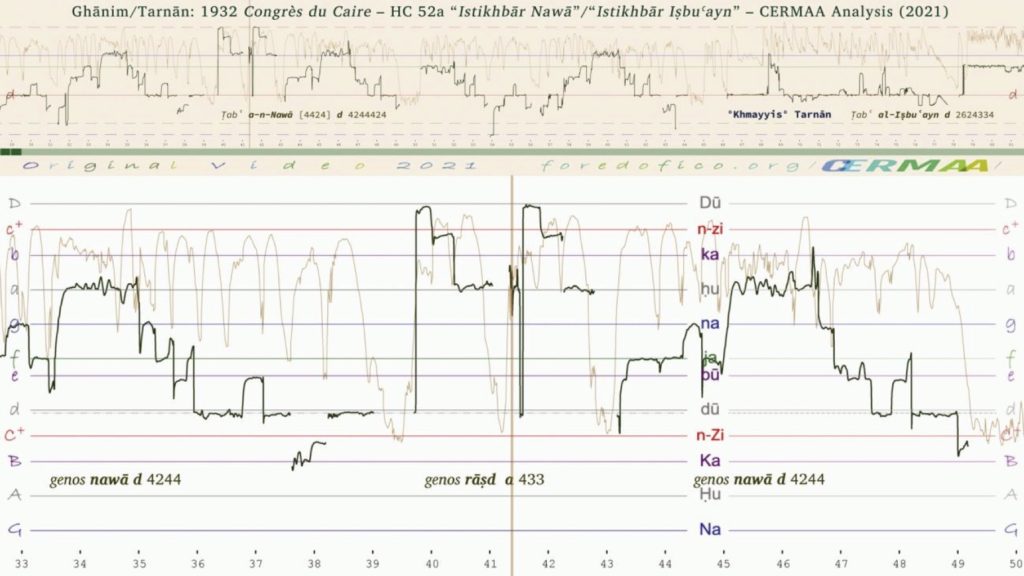

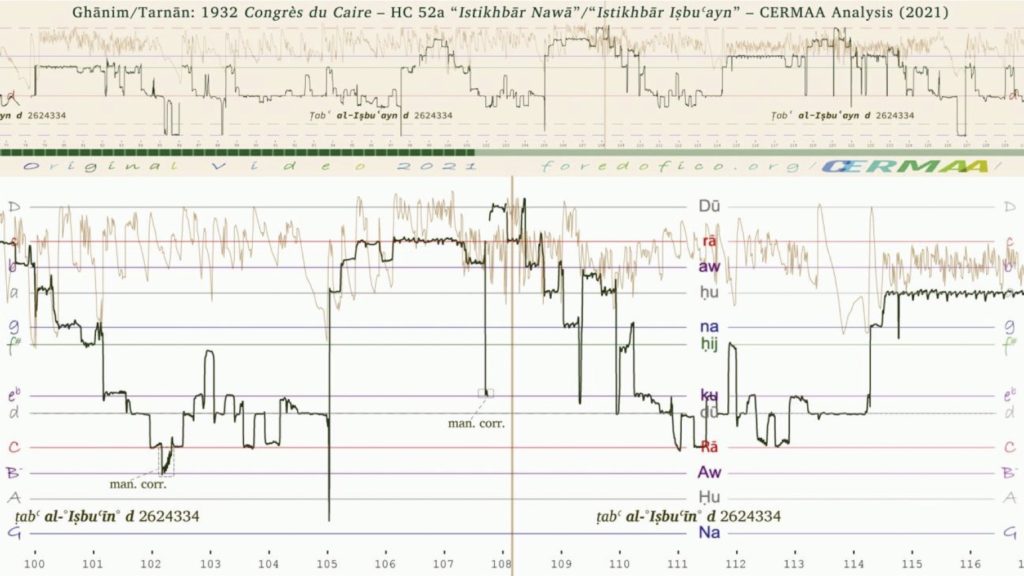

- Video 4: The ṭabʿ a-n-Nawā on rabāb, then ṭabʿ al-Iṣbuʿayn (or al-°Iṣbuʿīn°) on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 52a), (link to the video)

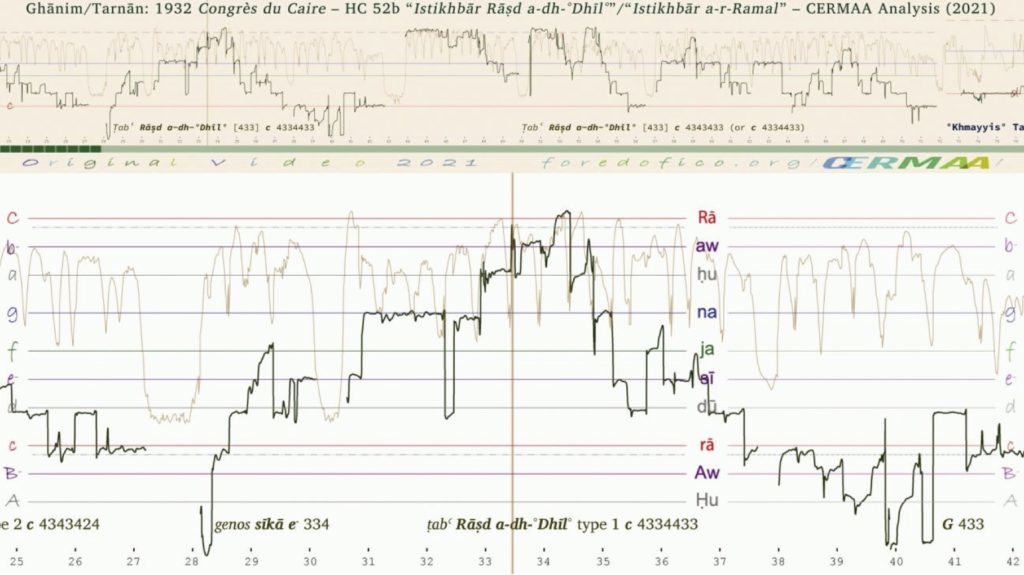

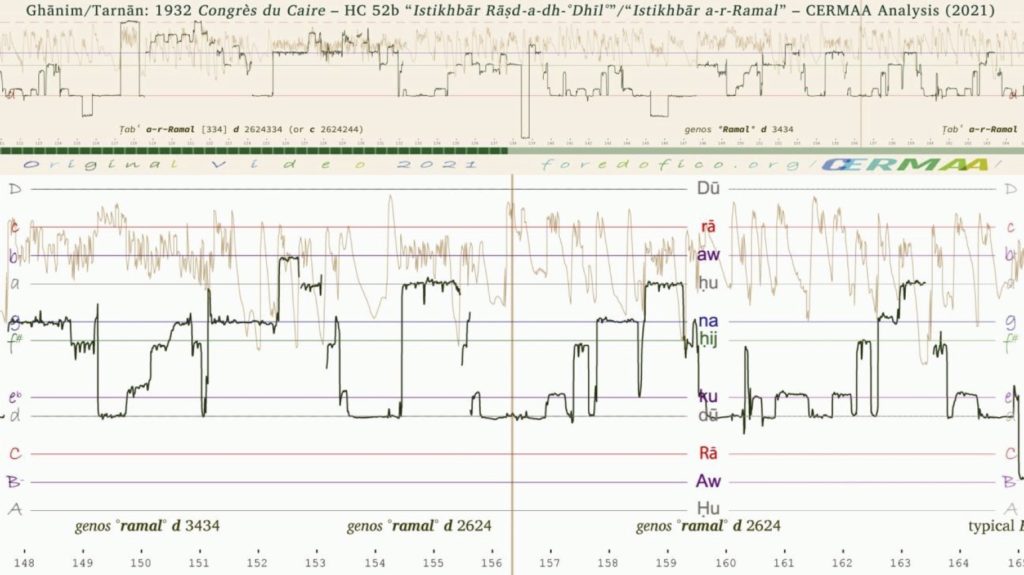

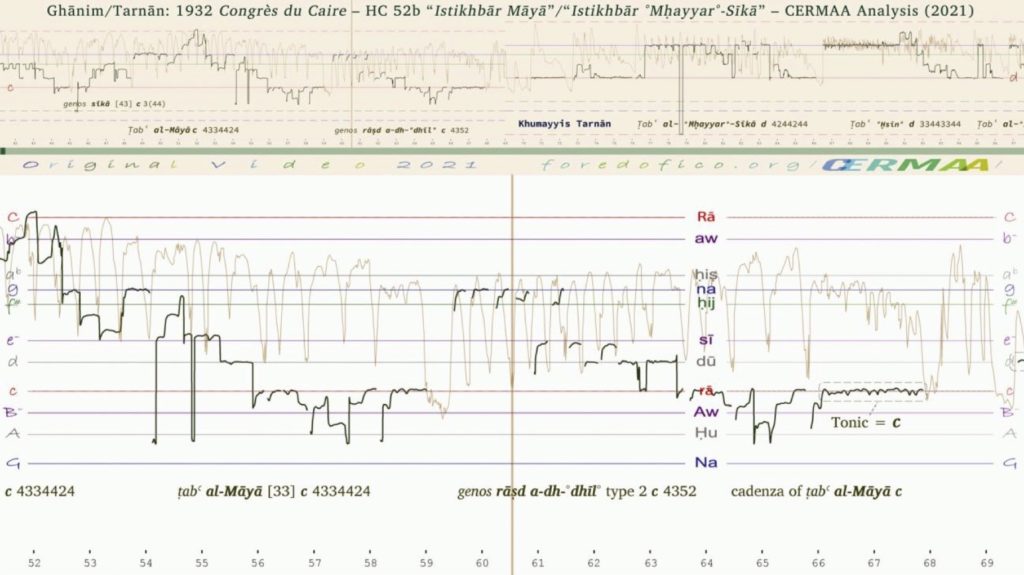

- Video 5: The ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° on rabāb, then ṭabʿ a-r-Ramal on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 52b), (link to the video)

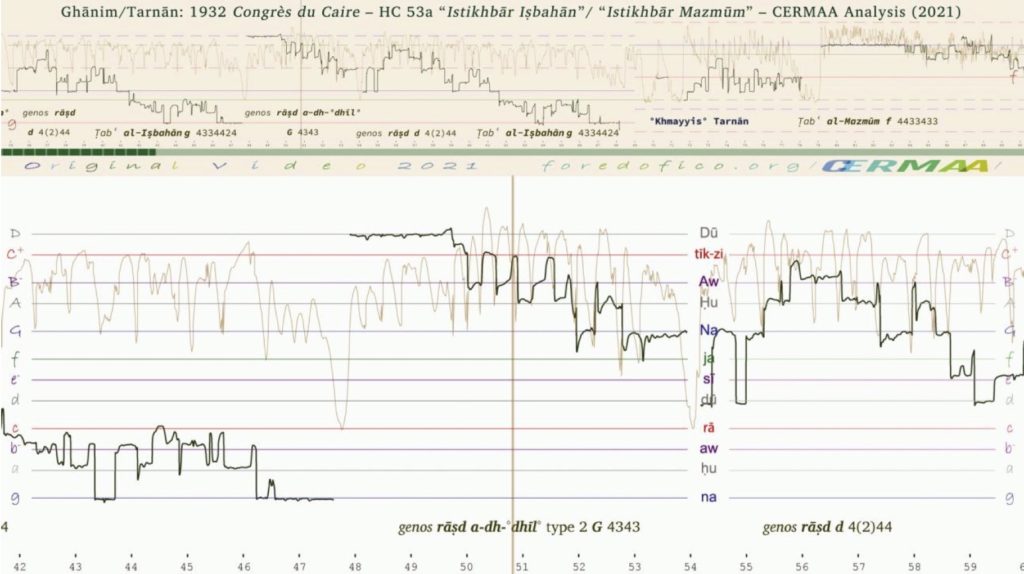

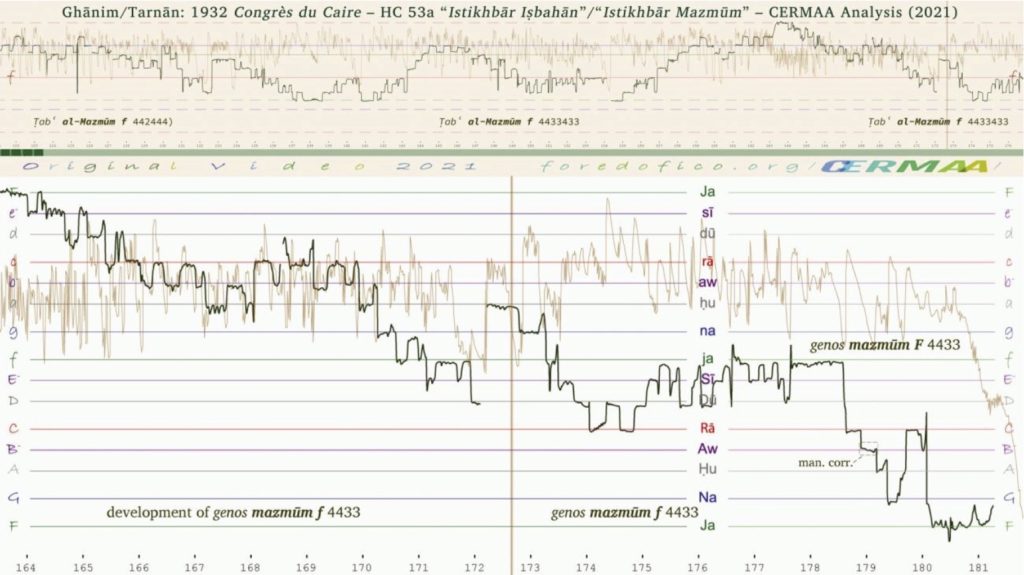

- Video 6: The ṭabʿ al-Iṣbahān on rabāb, then ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 53a), (link to the video)

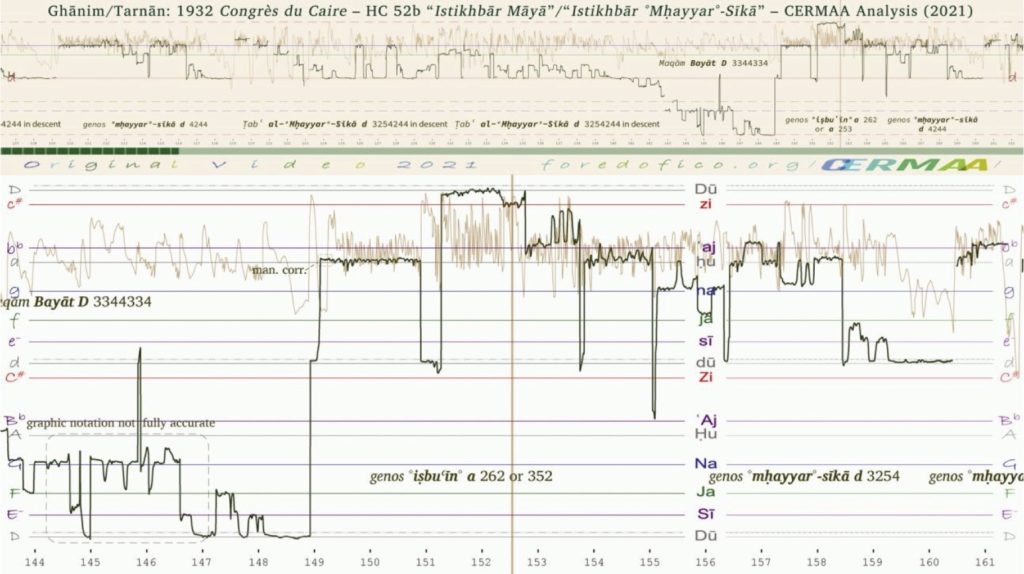

- Video 7: The ṭabʿ al-Māyā on rabāb, then ṭabʿ al-°Mḥayyar°12 -Sīkā on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 53b), (link to the video)

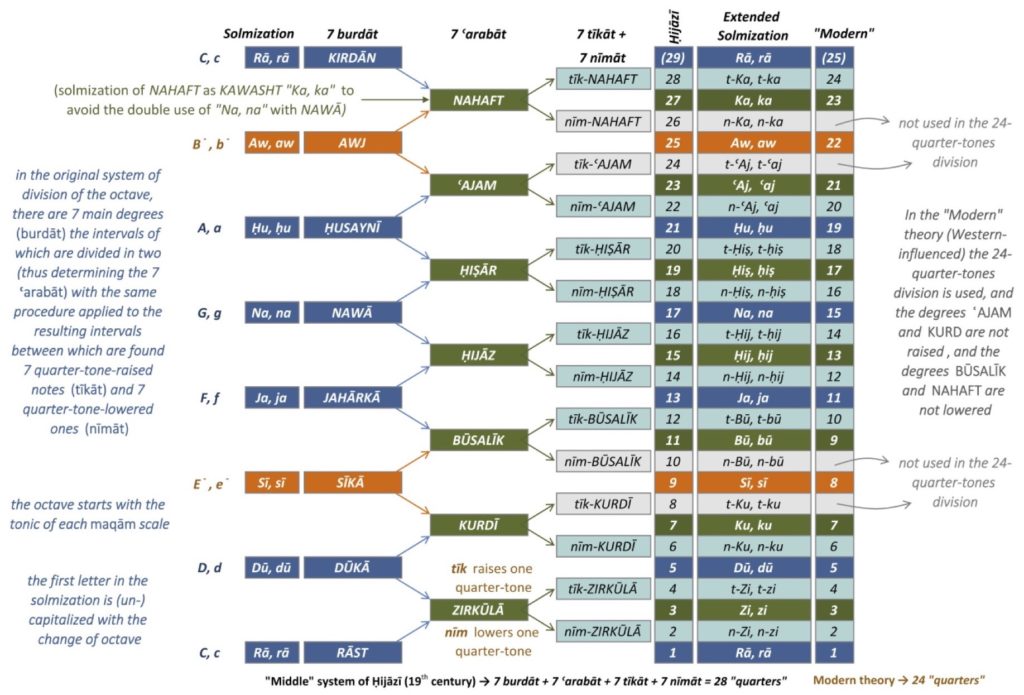

In all the video analyses, various graphic scales are used according to the main ṭubūʿ scales and to the identified modulations, using a Western literal notation on the sides and a central – shifted to the right – Arabic solmization following the one earlier proposed by Beyhom (Figure 2). The notes in the main, first scale (between the tonic and its upper octave – if any) are written with lowercase letters, while the initial letter is capitalized in the two neighbouring (upper and lower) octaves – this also applies to the English notation used for the scales; Finally, nīm- (lowering one quarter-tone) and tīk- (raising one quarter-tone) indications in the graphic scales are shortened as “n-“ and “t-“ thus, for example, “n-ḥij” for “nīm-ḥij” or “nīm-ḤIJĀZ”, equivalent to an approximate f+ (f raised by an approximate quarter-tone)13.

In the commentaries of the videos, 2 time indications may be used, mainly “s_a” (for “seconds of the analysis”) for the analysis as such, and possibly “s_v” (for “seconds of the video”) for the overall time (in seconds) of the video.

Some of the graphic scales can move slightly vertically to fit the possibly moving tonic or any other degree of the scale, with a horizontal dashed grey line showing the position of the original tonic15. Intervals of a scale are written (noted) as successive ascending multiples of a theoretical – and approximate in practice – quarter-tone, thus 4424442 for the tense (Western) diatonic scale of c on c, equivalent to c 4 d 4 e 2 f 4 g 4 a 4 b 2 C.

Lastly: All the musical pieces are identified under the number of the master recording which is provided in the latest available edition (2015) of the recordings of the Congrès du Caire16, for example for the Istikhbār Rahāwī by Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb, then the Istikhbār °Dhīl° by °Khmayyis° Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī°, CDC (for “Congrès du Caire”) HC 50a (identifier of the corresponding master recording containing the two istikhbārāt).

Tunisian ṭubūʿ at the 1932 Congrès du Caire

The original idea for this article was the analysis of all the istikhbārāt (improvisations) of Tunisian music contained in the 2015 edition of the music recorded at the Congrès du Caire of 1932. Unfortunately, one of the master recordings (HC 51a) reproduces a qaṣīda with mixed singing and ʿūd playing, the computer analysis of which is still problematic with the – till today – available tools. The other master recordings (HC 50 to HC 53, excluding 51a) are all divided in two (more or less)17 clearly distinguishable parts, with a first improvisation by Muḥammad Ghānim (Figure 3) on the rabāb, and a second one by °Khmayyis° Tarnān (Figure 4) on the ʿūd °ʿarbī°, which totals 14 different improvisations and ṭubūʿ (Tunisian “modes”). Due to the recordings date, however and as aforementioned, from the 1932 Congrès, and due to the particular technique of Tarnān, very limited parts of his performances had to be corrected manually, and signalled by the shortened terms “man. corr.” (for “manual correction”)18.

Figure 3. Muḥammad Ghānim and his rabāb at the 1932 Congrès du Caire.

Figure 4. °Khmayyis° Tarnān and his ʿūd °ʿarbī° at the 1932 Congrès du Caire.

In the 1988, 2 CD edition of chosen recordings of the 1932 Congrès du Caire, Bernard Moussali comments:

“The Tunisian ensemble was selected by d’Erlanger19 and Darwīsh20 as part of a strategy to reconstitute melodies of bygone years, as they conceived them. Muhammad Ghānim (c. 1880-1940) was encouraged to drop his current technique on the rabāb, which carried the basic melody line, in favour of a technique close to that of the violin: armed with a long, unusual bow, he provided embellishments and improvisations. °Khmayyis° Tarnān (1894-1964), student of Aḥmad a-ṭ-Ṭuwaylī (c. 1870-1933) began his career as a lutenist and an interpreter of Near-Eastern music. He was encouraged to learn the traditional vocal suites (maʾlūf) and to use the ʿūd °ʿarbī°, the lute of the family of the quwaytra, or °qwītra° in dialect (diminutive of qītāra, from the lndo-European ‘guitar’). He went on to become one of the masters of Tunisian music.”21

Bernard Moussali in (Various 1988, 146)

Were present with the musicians at the Congrès Mannoubi Snoussi22, ʿAlī a-d-Darwīsh and Ḥassūna Ibn ʿAmmār23. For the first time in history, an abridged version of a nūba in ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° was recorded (HC 40 to 45). The performance of the Tunisian musicians was an attempt “ ‘to go back to the basics’ that led to the establishment of the Music Institute of Rāshidiyya in 1934, and to the transcription of the traditional Tunisian heritage. […This] meant a good deal of reconstruction”.

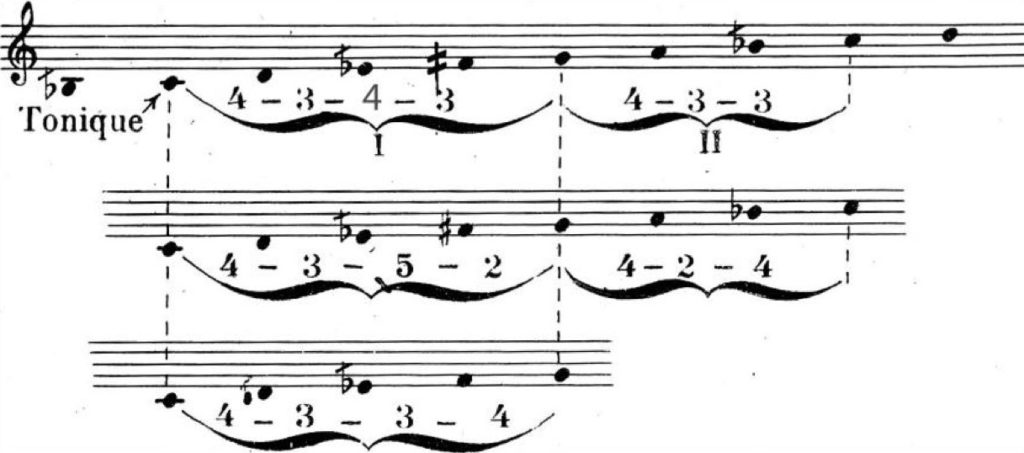

In the Tome 5 of La Musique Arabe by Erlanger24, the scales of the Tunisian ṭubūʿ – with examples for each of them – are notated apart (before the indexes) under fig. 144 to fig. 176. We relied for the graphical analyses on these notated scales and on Mannoubi Snoussi’s descriptions of the ṭubūʿ in his Initiation à la Musique Tunisienne25, as well as on Hamdi Makhlouf’s knowledge of the Tunisian repertoire.

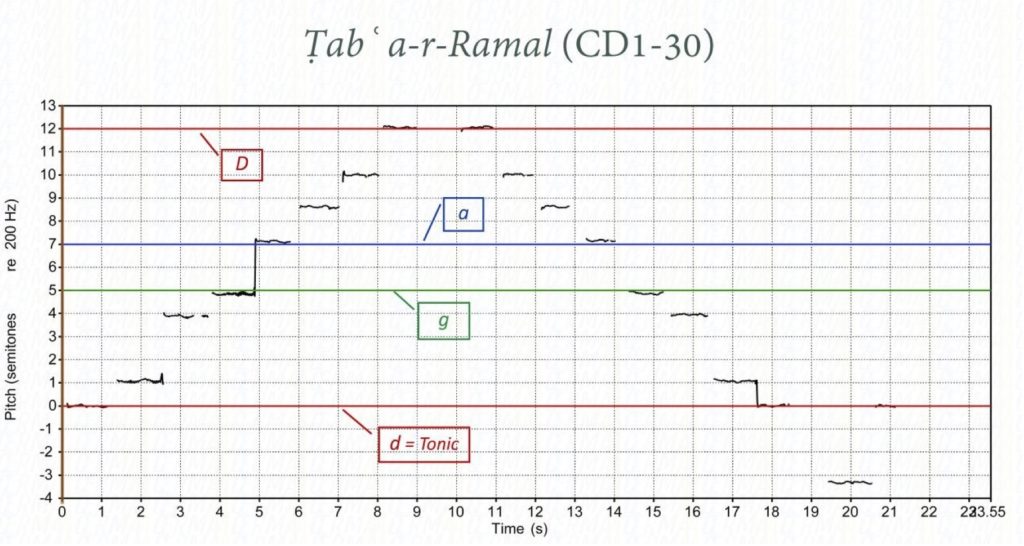

One main aim of these analyses was the comparison between theory and practice. A second aim was the identification of possible characteristics of the instrumental playing of the performers – and of the instruments. In each of the following sections, each comprising two istikhbārāt by, firstly, Ghānim then secondly Tarnān, a short video – based on a Power Point show – analyses the scale of the ṭabʿ – when given – as proposed in the accompanying CD 1 of Snoussi, to be compared with Erlanger’s notation reproduced as a figure in the text. The two descriptions are then compared to the practice through the performances of the two musicians, each of them in one ṭabʿ. Furthermore, Ghānim’s and Tarnān’s practices are rapidly compared to today’s teaching of the ṭubūʿ, when these practices differ one from another.

Important notice : As with Snoussi in his explanations, we use in the main text genos 26 and tetrachord denominations such as rāst, būsalīk etc. in the below explanations, knowing that the use – and naming – of these tetrachords in Tunisian ṭubūʿ is different from their use – and denominations – in Middle-Eastern maqām music. In order to give modern Tunisian musicology its due share, we have added a special section at the end of each ṭabʿ and istikhbār analysis, entitled “Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ XXX by YYY ZZZ” (and on orange background similar to the one of this notice), in which the sayr al-ʿamal is shortly described using the Tunisian terminology of the ṭubūʿ and genē, namely for the latter: rahāwī type 1 (433 in multiples of the approximate quarter-tone), rahāwī type 2 (or mujannab a-r-rahāwī 424), °dhīl° (433), ʿirāq (334), sīkā (344), °ḥsīn° (334), rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° type 1 (433) and type 2 (4253), pentatonic rāṣd 424, °raml° al-māyā 334, nawā 424, iṣbuʿayn (262 or 253 or 343), °ramal° 253, iṣbahān (433), mazmūm (442) and māyā (433).

➤ Analysis 1: The ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī by Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb, then ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° by °Khmayyis° Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 50a)

In these two first ṭubūʿ, some discrepancies between the two authors (Snoussi and Erlanger) as well as between theories and practices begin to reveal themselves.

First improvisation by Ghānim on rabāb: Ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī

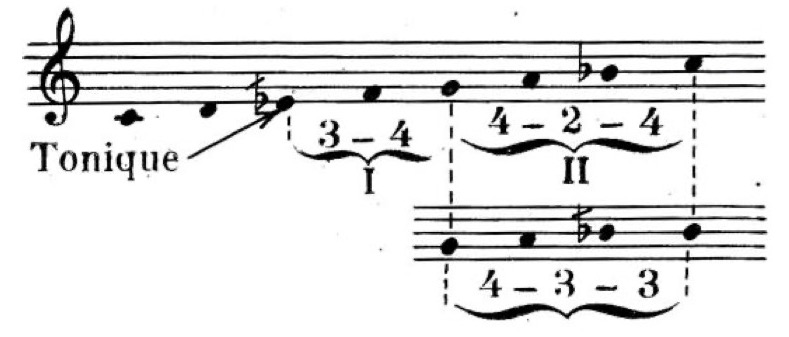

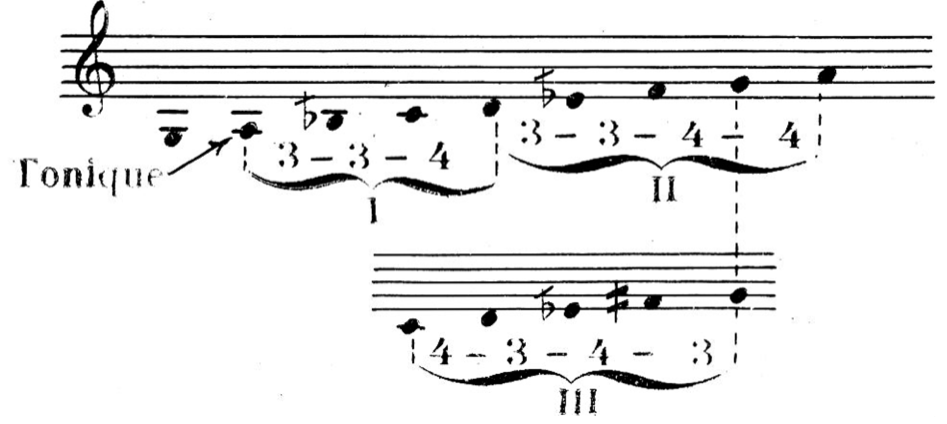

Ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī is the only ṭabʿ – among those analysed in this article – which is not explained in (Snoussi 2003)27; it is notated, with an example, on a tonic = c in (Erlanger 1949) with a mobile e (e– or eb – see Figure 5). The division of the scale in this notation favours a sub-tonic B– (or “B minus one quarter-tone”) while the main scale uses a bb within an upper būsalīk tetrachord g 424 preceded by alternatively a rāst 4334 or a būsalīk 4244 tetrachords on c.

Figure 5. Ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī as explained in Erlanger (Erlanger 1949, 5: mode no. V, fig. 152), with the French “Tonique” indicating the tonic; the lower pentachord is either c 4334 (rāst) or c 4244 (būsalīk) with a subtonic B–. (The second “3” interval of the initial pentachord was computer corrected by the authors; if the note is eb, the consecutive intervals between d, eb and f should evidently be 2+4.)

In his performance, Ghānim uses a range of a fifth above the tonic c and of a fourth below it. He uses a high A – which could be specific of ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī – in the lower tetrachord on G and B (plain)28 as a sub-tonic (in place of the B–) and three clearly delineated types of e, from eb to e (plain), with also an e– 29. These are substantial differences with the above notated scale, with an additional ʿajam pentachord c 4424 and another ʿajam tetrachord 442 on g (or at least on the lower G), and a more mobile third degree eb e– e. (Figure 6)

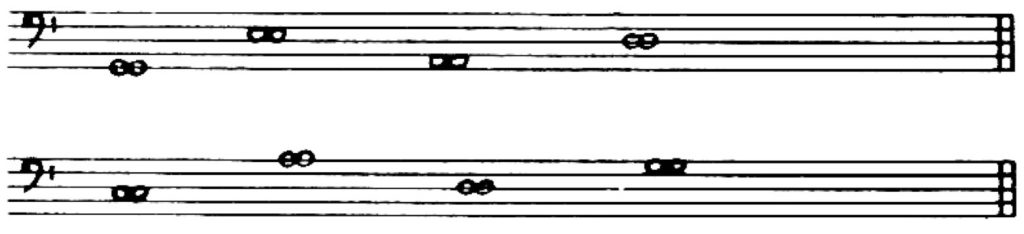

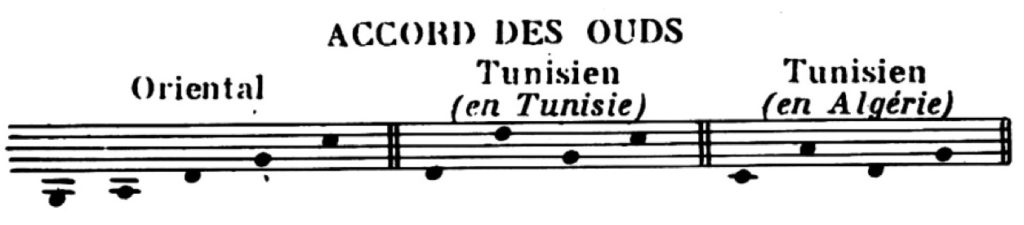

We can also notice (for example around 49 s_a) small discrepancies between the tonic of the rabāb for this ṭabʿ and the tonic played occasionally (in parallel) by Tarnān. This is most probably due to the fact that the ʿūd °ʿarbī° of Tarnān, generally tuned in d d’ g c’ (Figure 7 and Figure 8), has an unstopped c, while Ghānim’s rabāb has two strings tuned as g and d, and his tonic c must be stopped on the g string.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī by Muḥammad Ghānim

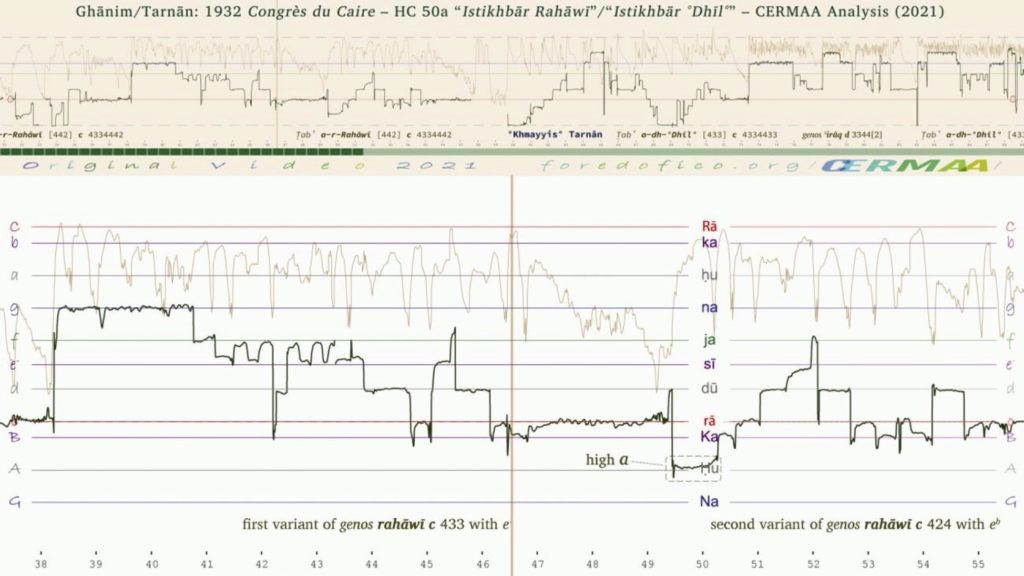

(3.* s_a): Tonic = c. (5.*-21.* s_a): exposition of the main genos rahāwī c 433/424 of the ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī. (5.*-14.* s_a): rahāwī genos c 433 with e–. (15.*-21.* s_a): variant “mujannab” of genos rahāwī c 424 with eb. (22-31 s_a): complete scale of ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī, followed by (31.*-35 s_a) by descents to the lower G and back to the tonic (36-38 s_a). (38.*-48.*): 1st variant (with e–) of rahāwī c 433; (49-58 s_a): 2nd variant “mujannab” of rahāwī c 424 (with eb) and end.

Detailed segmentation/Analysis

- 5-14 s_a: rahāwī c type 1 433

- 15-21 s_a: rahāwī c type 2 c 424 (a.k.a. mujannab a-r-Rahāwī)

- 22-31 s_a: rahāwī c type 1

- 31-38 s_a: rahāwī c type 1

- 38-49 s_a: rahāwī c type 1

- 49-51 s_a: rahāwī c type 2 424 (a.k.a. mujannab a-r-Rahāwī). The descent to YĀKĀ (14 s_a and 33-34 s_a) seems to be characteristic of the sayr al-ʿamal of the ṭabʿ.

Second improvisation by Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī°: Ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl°

In (Snoussi 2003, 47–48), the author explains that the ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° is close to the “Oriental” maqām Rāst on c 433(4)433 with the adjunction of a lower rāst tetrachord (a “°dhīl°” in Tunisian vernacular, or “dhayl” in classical Arabic) 433 on (lower) G (Video T.1), the same as with Erlanger (Fig. 9), who notates, however and further, a highly mobile e (from eb to e plain, and through e–) resulting further in the būsalīk tetrachord on c or on d, and with a higher extension – intermingled with the 433 tetrachord on g – consisting in a sīkā (or ʿirāq) trichord 34 on b–.

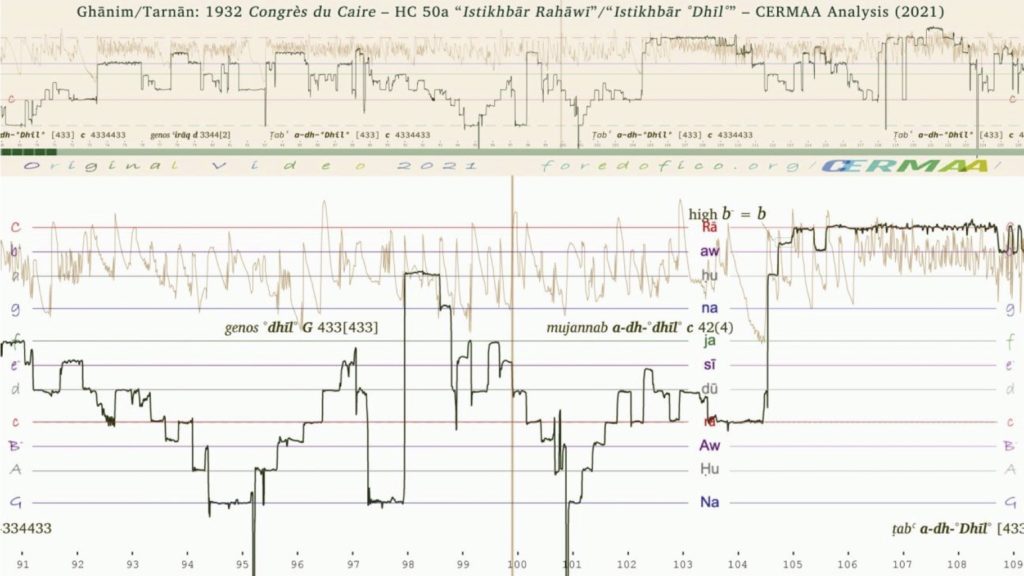

The theoretical highly mobile e in ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° resembles the highly mobile e in Ghānim’s performance for the ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī (see above). The energetic performance of Tarnān on the ʿūd °ʿarbī°, which encompasses a full octave + fifth, is however much more straightforward, interval wise (Figure 10), as Ghānim’s, although the e–can be occasionally a little high (92, 99 and 100.* s_a – but not a straightforward e), but with the occasional use of eb as at 102.* s_a more as passing micro-modulation than as an effective modulation to genē būsalīk 424 on c. Note also the use of a very high b– at 105 s_a and of a bb at 88.* s_a, and the unstable tuning of the tonic, very clearly discernible at the end of the piece (around 176-177 s_a). Finally, note the passages 60 to 73 s_a, 128 to 137 s_a and 156 to 167 s_a which correspond to (what has become) a characteristic “must do”31 passage – a melodic-rhythmic formula – for this ṭabʿ.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° by °Khmayyis° Tarnān

(59.*-73 s_a): exposition of the scale of ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° c 4334433 with a characteristic phrase of the ṭabʿ. (73.*-82.*): this part is typical of ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq d 33442(44)32 [ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq comes after the °Dhīl° in the succession of nawbāt and ṭubūʿ]. (83-104 s_a) back to the scale of ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° c 4334433 then development of the scale (105-128 s_a) in the upper part mainly. (128-137.* s_a): return to the initial characteristic phrase. This is followed by a come-back (137.*-152.* s_a) to ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq d 334433(4) with (152.*-167.*) a reiteration of the initial characteristic phrase in ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° c 4334433, and a final short exposé (168-177.* s_a) of this phrase encompassing (nearly) the whole range from upper C to lower G and back to the tonic c.

Detailed segmentation/Analysis

- 60-73 s_a: °dhīl° c 433 with low e– (also mujannab)

- 60-66 s_a: micro stop on DŪKĀ d → genos ʿirāq d (334)

- 67-69 s_a: characteristic descent to YĀKĀ (probably a °dhīl° G 433)

- 69-73 s_a: °dhīl° with mujannab c 424

- 73-82 s_a: ʿirāq DŪKĀ d (334)

- 83-104 s_a: °dhīl° c 433 with mujannab c 424, with multiple micro stops

- 83-89.* s_a: extended ʿirāq DŪKĀ d (334)

- 89.*-95 s_a: °dhīl° YĀKĀ G 433 or 442

- 101-104 s_a: °dhīl° with mujannab c 424

- 104-118 s_a: °dhīl° c 433 [close to the formulation of a raṣd a-dh-°dhīl° type 1 c 433(4)] + exploration of the upper register

- 118-128 s_a: °dhīl° (development of the preceding phrase)

- 128-137 s_a: similar to 60-73 s_a above (1st phase)

- 137-143 s_a: ʿirāq DŪKĀ d (334)

- 143-167 s_a: similar to 60-73 s_a above (1st phase)

- 168-177 s_a: Typical concluding formula (cadenza) of the °Dhīl°

All in all, both performances are very rich and interesting with, however and as could be expected, sometimes consistent differences between (written, notated) theory and practice.

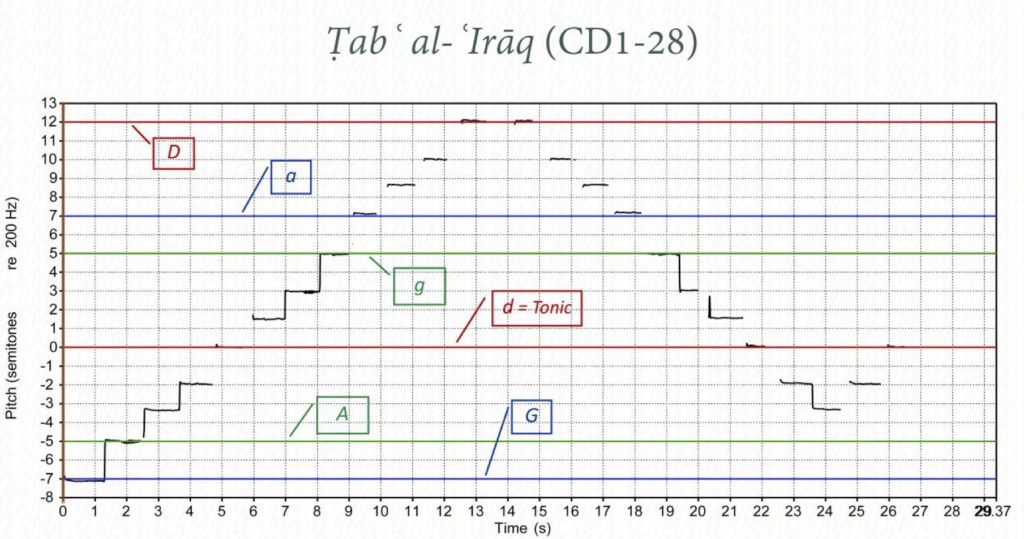

➤ Analysis 2: The ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq by Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb, then ṭabʿ a-s-Sīkā by °Khmayyis° Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 50b)

This was not an easy analysis, mainly because of the differentiation between the tonic of each mode (d and e– – see Figure 11 and Figure 15) and the characteristic note of each (ʿIRĀQ33 – b– – for the first, more classically SĪKĀ – e– – for the second).

First improvisation by Ghānim on rabāb: Ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq

Manoubi Snoussi describes the scale of ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq34 as based on d and composed of two conjunct tetrachords (Video T.2), the first a bayāt 334 tetrachord on d (or d e– f g)35 and the second being a rāst 433 tetrachord on g (or g a b– c), which is a first difference with Erlanger (Figure 11) for whom the second tetrachord is in fact a trichord of the type būsalīk (or “minor”) g 42 (with a bb instead of b–). However, Snoussi also notes that a supplementary lower rāst pentachord on (lower) G (or G A B– c) complements the scale in the lower octave, which gives the complete scale G A B– c (= tonic) d e– f g a b– c for Snoussi, with a minor difference with Erlanger as the b is flat in his notation, or G A B– c (= tonic) d e– f g a bb.

Snoussi further explains that:

“[a]fter a fortuitous36 stop on the lowest note of this supplementary pentachord (lower G), the movement [of the melodic line] rises to carry out the final stop on the tonic d. The cadenza for the resolution of the mode uses a fall of fourth (from dominant37 to tonic), which is the main characteristic of this mode.”38

Snoussi, 2003, p. 55

Effectively, Ghānim uses in his performance a range from (lower) G to c, encompassing one octave + one fourth, with the main scale G [4334]39 c (= tonic) 33442. The lower B– seems to be rather theoretical as when acting as a leading tone (see for example Figure 13 and the video around 21-23 s_a) it is clearly sometimes closer to a plain B – if not slightly higher. Similarly, the e– (same figure) is also (very) high, which differs considerably from the near exact quarter-tone lowered e with Snoussi (Figure 12).

As for the cadenza exposed in Snoussi’s quote – with the temporary stop on lower G then a descent from the fourth degree to the tonic, it is masterfully executed by the performer no less than three times, around 37-43 s_a, 58-65 s_a, and finally around 76-81 s_a (Figure 14).

Other peculiarities of the performance are the use of sometimes high As (for example 49-59 s_a) and fs (for example 62.* s_a). Finally, let us note that this performance by Ghānim lasts longer (81 seconds in all) than the previous one (less than 60 seconds), which leaves less time for Tarnān to develop his istikhbār.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq by Muḥammad Ghānim

(3.*-13.* s_a): A reminder of ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° C 4334(433) with high e– and f. (17.*-23.* s_a): confirmation of ṭabʿ a-dh-°Dhīl° c 433(4433)40. (24-32 s_a): ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq G [4334] d = tonic 334(4334) with high A, B–, e– and f. (32-43 s_a): a new ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq G [4334] d = tonic 33443(34) with high A, B–, e– and f. (43-81): ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq G [43347] d = tonic 33443(34) with a °Dhīl° C 4334(433) between 65 and 72 s_a.

Detailed segmentation/Analysis

- 3-13 s_a: °dhīl° (RĀST) C 433 ; note a very high e (almost e plain) and the high f (practically f+)

- 14-23 s_a: °dhīl° (RĀST) C 433 ; note a micro-stop on d = dū around 17 s_a (maybe a hint to ʿirāq d = dū 334?) ; note also the very high A (practically A#) at 22 s_a

- 24-43 s_a: ʿirāq d = dū 334

- 24-28 s_a: ʿirāq d = dū 334 / micro – stop

- 28-31 s_a: °dhīl° 433 YĀKĀ = G = Na / stop

- 32-36 s_a: ʿirāq d = dū 334 / micro – stop

- 36-38 s_a: °dhīl° 433 YĀKĀ = G = Na / stop

- 38-43 s_a: ʿirāq d = dū 334 / stop. Note that the A is still very high, as well as B– and, at 25-26 s_a, f.

- 43-64 s_a: ʿirāq d = dū 334

- 43-47 s_a: successive fourths (characteristic of ṭabʿ al-ʿIrāq)

- 47-50 s_a: sīkā 343 on Aw (B–) / note the high f (f+) and high e– (nearly e) ; note also that this is probably a short modulation to ṭabʿ a‐s‐Sīkā, or simply denotes the possibility of a possible sīkā genos on B– in ṭabʿ al‐ʿIrāq

- 50-56 s_a: ʿirāq d = dū 334 / micro – stop

- 56-59 s_a: °dhīl° 433 YĀKĀ = G = Na / stop

- 59-64 s_a: ʿirāq d = dū 334 / stop

- 65-81 s_a: ʿirāq d = dū 334

- 65-71.* s_a: °dhīl° (RĀST) c 433 / stop

- 72-77 s_a: °dhīl° 4334[334] YĀKĀ = G = Na / stop

- 77-81 s_a: ʿirāq d = dū 334 / stop

Note: The stops of Ghānim on YĀKĀ = G = Na could also be understood to denote a genos °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq – the composition of which is traditionally given as 4334 but which could well be 5234 – instead of a °dhīl°.

Second improvisation by Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī°: Ṭabʿ a-s-Sīkā

The second improvisation in this recording (by Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī°) has a different tonic which is e– (Figure 15). Snoussi explains (Video T.3):

“The scale of this mode is composed of one trichord and one tetrachord conjuncted by a common note which plays the role of a dominant. The trichord is of the sīkā type, namely 3/4 tones, 4/4 tones, which corresponds to the notes: e – 1/4 tone, f, g. The tetrachord is of the type rāst, namely 4/4 tones, 3/4, 3/4, which corresponds to the notes: g, a, b – 1/4 tone, c. In the course of the evolution of the melodic movement, the rāst tetrachord is incidentally replaced by a tetrachord of the type ḥijāz, the Tunisian variant, namely 3/4 tones, 5/4, 2/4, which corresponds to the notes: g, a – 1/4 tone, b, c (with the b less ‘tense’ than the plain b).”41

Snoussi, 2003, p. 56-57

The ḥijāz tetrachord is not mentioned in Erlanger’s notation (Figure 15), in which is added a possibility for a būsalīk upper tetrachord on g, which is in fact the main upper tetrachord, the rāst tetrachord being the variant.

Tarnān uses de facto a range of one octave + one sixth, from (lower) D (119 s_a) to c (mainly around 141.* s_a – see Figure 16). His pitches are much closer to the theoretical ones in the zalzalian (bayāt and rāst) version (same figure), with a rather low D (around 151.* and 157.* s_a) and one use of a very high f around 170 s_a – which could be considered as a taṭrīz (“temporary inlay”) as with the Bb at 161.* s_a – but nonetheless no clear insertion of a “Tunisian ḥijāz” g 352 except for the use of a– at 100-101 s_a, which could be a hint to such a tetrachord.

All in all, a rather straightforward performance of ṭabʿ a-s-Sīkā in its zalzalian42 version.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ a-s-Sīkā by °Khmayyis° Tarnān

(84.* s_a): Tonic = e–. (86-96): exposition of ṭabʿ a-s-Sīkā e– [43]34433(43) with a high f, notably at 90-91.* s_a. (97-119 s_a): development of ṭabʿ a-s-Sīkā [43] e– 34433(43) but with a very low a (nearly = ab but most probably a–), and a passing low d at 107-108 & 110-111 s_a. (120-129 s_a): Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° type 1 C 433442(4) (with ʿaj = bb and tīk-ḥiṣ = a–). (129.*-136.*): Sīkā [43] e– 34433(43) with however starting bb. {Or Sīkā 34424(43).} (136-144 s_a): °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq g 43343. (144-148.* s_a): Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° type 1 4334433 on c. (148.*-164 s_a): ṭabʿ a-s-Sīkā E–[3443343] e– (= tonic) 344334(3). Conclusion (164.*-179 s_a) with ṭabʿ a-s-Sīkā e– [43]34433(43) using a very high f (= f+).

Note: Tarnān does not use the two main genē iṣbuʿayn G 343 and rāṣd a-dh°Dhīl° type 2 on F 4343. He just uses the melodic path (in a cadential formula) passing through the notes of these genē at 97-119 s_a. The same for the main genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā G 424, which he uses “en passant” (passing through the notes) at 159-164 s_a.

➤ Analysis 3: The ṭabʿ a-r-Rāṣd by Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb, then ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā by °Khmayyis° Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 51b)

First improvisation by Ghānim on rabāb: Ṭabʿ a-r-Rāṣd

The first theoretical (or practical) difference about this ṭabʿ is its name: in the title for Erlanger’s notation (Figure 17) the adjective ʿabīdī is added between brackets, while Snoussi explains44 that this adjective is added by Tunisian musicians in relation with the “black African slaves” (ʿabīd) “the music of which is also pentatonic”. Snoussi further explains (see Video T.4):

“It should be noted that, apart from the particular pronunciation of its name [when compared with the Near-Eastern, Turkish or Persian Rāst], the Tunisian – or better say Maghrebian, or even better Hispanic-Arabian – mode Rāṣd features, on the other hand, something which distinguishes it clearly from its oriental homonym. This particularity consists in the ‘leap’, or the frequent and deliberate omission, in the course of musical pieces composed in this mode, of one degree in the one or the other of its constitutive tetrachords, which gives the melody a characteristic pentatonic nature”45.

Snoussi, 2003, p. 44.

There are, on the other hand, consistent differences with Erlanger in Snoussi’s description of the scale of this ṭabʿ (compare with Figure 25):

“Its scale is a disjunct octave, composed of two tetrachords separated by a disjunctive tone comprised between the sub-dominant (c) and the dominant (d) which have, as a consequence, the same importance in the melodic movement. Both tetrachords are of the type rāst, namely 4/4 tones, 3/4, 3/4, which corresponds to the notes: g, a, b – 1/4 tone, c for the first tetrachord; and to the notes: d, e, f + 1/4 tone, G for the second tetrachord. The notes which are deliberately omitted in the course of the composition of the melody are the (b – 1/4 tone) in the first tetrachord, and the (f [+ 1/4 tone]46); these are generally omitted in the descending direction. [Moreover,] [t]he second tetrachord when it is used with no omissions of either of its passing notes, is sometimes replaced by a būsalīk type tetrachord, namely 4/4 tones, 2/4, 4/4, which corresponds to the notes: d, e, f, G”47.

Snoussi, 2003, p. 45

This description consistently differs from Erlanger’s notation, in that the tonic with Erlanger is d, with two joined (in place of disjunct) upper tetrachords – the first (lower one) of which can take the form of a būsalīk 424 on d and the second (upper one) of which can take the form of a rāst 433 on g – and with a lower (also ʿajam 4424) pentachord on (lower) G.

The performance of Ghānim underlines a scale G A B C (tonic =) d e f g a b c48 encompassing one octave + one fourth. The upper as are generally high, with rare uses of a (slightly) lowered e (16.* s_a) with a frequently omitted f in the upper tetrachord d e f g in descent (the “leap” of Snoussi – for example at 43.* s_a) and a complete absence of upper b– (b “natural” is used instead – see 27 and 29.* s_a, as well as Figure 18). The notes of the [C] d e f (when not reaching G) tetrachord use f in ascent (for example around 51 s_a).

These characteristics partly complement, confirm and contradict both theoretical explanations by Snoussi and Erlanger.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ a-r-Rāṣd by Muḥammad Ghānim

(2.*-6 s_a): exposition of the descending lower rāṣd G 4424 pentachord with the omission of the b in descent. (6.*-62.* s_a): development of the middle octave d e f g a b c with frequent stops (including the final one) on the tonic d, and the use (as stated above) of high as and the omission of the f in descent.

Second improvisation by Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī°: Ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā

Snoussi49 mentions a as a tonic for this mode, as with Erlanger (Figure 19). He further describes (see Video T.5):

“The scale of this mode is a conjunct octave, I mean by that that it is composed of two conjunct tetrachords, connected through a common note; the [whole] tone which completes the octave is placed in the high register. The first tetrachord is of the bayāt type, namely: 3/4 tones, 3/4, 4/4; this corresponds to the notes: a, b – 1/4 tone, c, d. The second tetrachord is of the rāst type, namely: 4/4 tones, 3/4, 3/4; this corresponds to the notes: d, e, f + 1/4 tone, g. While descending, however, ‘f’ natural is used in place of the augmented ‘f’, which gives the genos jahārkā on ‘c’.”50

Snoussi, 2003, p. 47.

Once again, there are serious differences between the two descriptions by Snoussi and in Erlanger, with both authors giving, however, this time the same tonic for this ṭabʿ.

The istikhbār by Tarnān – as energetic as ever – encompasses one octave and one fifth, from the sub-tonic G to the upper D (Figure 20), on a plain zalzalian scale based on a 3343344[334] and reaching the sub-tonic in the lower range. The f is rarely slightly raised (for example at 66.*, 142.*, 160 and 162 s_a), it is however replaced from the onset (and only this once) by an f# at 67 s_a (Figure 20). The B– may also be performed in a slightly high position (as at 109.* s_a) as with the e– (see around 117 s_a for an example) with frequent use by the performer of the sympathetic (unstopped) strings of his ʿūd (around 75, 82, 88, 91.* s_a, etc.) which prevents sometimes a completely accurate graphic notation of the main melody.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā by °Khmayyis° Tarnān. General description:

This istikhbār in the ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā is based on ḤUSAYNī (= ḥu = a) as a fundamental tonic note. It seems well that this is the original (traditional) tonic of the ṭabʿ, according to Erlanger’s notation above, and to Ṣalāḥ al-Mahdī in one recorded lesson51. Note that nowadays °Raml° al-Māyā is considered to be similar to ṭabʿ °Ḥsīn° with some specificities of interpretation, such as the preferred use of the upper register of the ṭabʿ, and the genē that can be used. This is (probably) also why it is today theorized as having a tonic dū = d = DŪKĀ.

The three phases of the improvisation follow a nearly similar development, in which °Khmayyis° Tarnān alternates between three genē in nearly the same way: rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° on do = c = rā in its two variants/types (4334 or 4343), then °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq on Sol = G = Na 4334(33) then (two) °ḥsīn° ré = d = dū and la = a = ḥu or A = La = Ḥu 3344.

The use of the double closing descending °ḥsīn° in the three clearly delineated phrases/parts/phases of the istikhbār confirms it as a closing cadenza of the ṭabʿ, from which the jahārkā genos (in Tunisian genos theory a mazmūm), promoted by Snoussi, is completely absent. Consequently, the use of the jahārkā genos may correspond to a form of alteration/deformation of the original ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā or, as another possibility, may result from a confusion with ṭabʿ °Ḥsīn°-Ṣabā (a variant of ṭabʿ Ḥsīn, the sayr al-ʿamal of which focuses on the jahārkā genos on f).

Detailed segmentation/Analysis

PHASE 1

- (64-76 s_a): genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° – type 1 (do – c – rā) 4334. This introductive segment comprises two levels of treatment of the melody: a first level (66-71 s_a) showing fundamental specificities of the melodic evolution of the ṭabʿ which are the focus on the 7th degree of the scale and the beginning in the high register. The second level is characterized by the use of a genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl c 4334 in place of the “usual” jahārkā c 4424.

- (77-82 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (ré – d – dū) 3344. The °ḥsīn° d 3344 genos (on the fourth degree of the scale) seems to be a natural consequence of the use of the preceding rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl°. It seems, however, that this genos is neglected in the theory of ṭabʿ °Raml°-al-Māyā today.

- (83-88 s_a): °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq (Sol – G – Na) 4334. The descent to the G (lower seventh degree of the scale) is one of the specificities of the °Raml° al-Māyā. In today’s ṭubūʿ theory, this is just mentioned as is. However, it is sometimes mentioned as a genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° (here on G). Tarnān’s treatment is, however, completely different: the lahja (“accent”) he uses is the accent of a °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq 4334(334) on G (85-88 s_a, with a very high b– at 87-88 s_a).

- (89-92 s_a): genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° – type 1 (do – c – rā) 4334

- (93-97 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (ré – d – dū) 3344

- (97-104 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (la – a – ḥū) 3344 (with bū)

The succession of two °ḥsīn° genē in descent is clearly – according to Tarnān, at that time and in this istikhbār – a melodic signature of the ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā, which is lost today from traditional music. While exposing the ṭabʿ in this first phrase/phase, Tarnān seems also to impose genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° as the main, essential genos of ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā.

PHASE 2

- (104-110 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (La – A – Ḥū) 3344. Genos °ḥsīn° (on upper A) is a fundamental component of ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā as well as a confirmation of the importance of the higher register of the ṭabʿ. The whole is a different way of starting an istikhbār in this ṭabʿ. Note the very high B-, practically a B.

- (110-116 s_a): genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° – type 2 (do – c – rā) 4343 (with nīm-ḥij)

- (116-121 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (ré – d – dū) 3344

- (121-126 s_a): °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq (Sol – G – Na) 4334

- (126-129 s_a): genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° – type 2 (do – c – rā) 4343 (with nim-ḥij) * (129-133 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (ré – d – dū) 3344

- (133-138 s_a): °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq (Sol – G – Na) 4334. Usage of the same trio of genē in the same succession as with the first above phrase. Tarnān confirms thus the rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° as the main genos using here its second variant (“type 2”) with a very high f at 112.* s_a and a relatively high e– just before 113 s_a.

- (126-129 s_a): genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° – type 2 (do – c – rā) 4343 (with nim-ḥij)

- (129-133 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (ré – d – dū) 3344

- (133-138 s_a): °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq (Sol – G – Na) 4334. Let us here just note the repetition of the same trio rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl°, °ḥsīn° and °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq.

- (138-143 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (ré – d – dū) 3344

- (143-150 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (la – a – ḥū) 3344 (with bū). Once again the same cadential formula (succession of two °ḥsīn° genē)

PHASE 3

- (151-157 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (La – A – Ḥū) 334(4). Same start as with the second phrase, where Tarnān insists on this specificity of the ṭabʿ. Note again the very high B–, practically a B.

- (157-164 s_a): genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° – type 2 (do – c – rā) 4343 (with nīm-ḥij). Once again a rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° type 2

- (165-168 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (ré – d – dū) 3344

- (168-176 s_a): genos °ḥsīn° (la – a – hū) 3344 (with bū). For the third time here the same cadential formula (succession of two °ḥsīn° genē)

Conclusion of the Analysis

Erlanger was definitely right in his transcription/notation of ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā: the jahārkā genos on the third degree c of the scale seems to be a “novelty”52 and has erased the memory of genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° as a main genos of the ṭabʿ. It seems that genos °ḥsīn° on the fourth degree (which was a fundamental component of the signature of the ṭabʿ) has equally become “forgotten” in favour of a °mḥayyar°-sīkā on the fourth degree d – the latter being today taught to be the main genos of the ṭabʿ.

Important note: one of the most popular songs in Tunisia, to which all teachers of Tunisian ṭubūʿ allude to as a perfect example of ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā, is accessible at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xebtLx9C-wo or at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jNMuXR_Pf7A. The reader can realize the impressive changes which have affected the ṭabʿ since this istikhbār of °Khmayyis° Tarnān.

Both performances show that, at least around 1932 and with these two performers, the theory of the ṭubūʿ still needs adjustments, and that many other analyses must be undertaken before a definitive description – if possible at all – can be established.

➤ Analysis 4: The ṭabʿ a-n-Nawā by Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb, then ṭabʿ al-°Iṣbuʿīn° by °Khmayyis° Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 52a)

These two istikhbārāt will show even less conformity with theory as the ones before, with Tarnān’s ʿūd technique creating slight disturbances as before for the graphic notation.

First improvisation by Ghānim on rabāb: Ṭabʿ a-n-Nawā

Manoubi Snoussi gives d as a tonic for this ṭabʿ and adds (see Video T.6):

“The scale of this mode is a disjunct octave, meaning composed of two disjunct tetrachords, […]. The first tetrachord is of the type būsalīk, namely: 4/4 tones, 2/4 tones, 4/4 tones, which corresponds to the notes: d, e, f, g. The second tetrachord is of the bayāt type, namely: 3/4 tones, 3/4, 4/4, which corresponds to the notes: a, b – 1/4 tone, c, d. The second degree of the second tetrachord (b – 1/4 tone) is frequently omitted in the descending course of the movement, which gives the melody a striking pentatonic effect.”53

Snoussi, 2003, p. 54.

As usual, some differences with the notation of the same ṭabʿ in Erlanger exist as in the latter: the second tetrachord of Snoussi is the first, but in the lower range (Figure 21), and the upper tetrachord is no more of the bayāt type, but also a būsalīk 424 on a, with the possibility of omitting, this time, the b. The “middle” pentachord on d is of the būsalīk type 4244 but with the possibility of using a quarter-tone raised f (f+) which adds still another difference in the description between the two authors. Moreover, the tonic is given in Erlanger as the (lower) a.

Further: a pattern seems to become patent in the differences between the two descriptions, which is the marked preference in Erlanger for conjunct pentachord-tetrachord descriptions, whenever with Snoussi there is a marked preference for a plain tetrachordal (plus one whole-tone) description54.

In Ghānim’s performance, we can barely distinguish from the onset a b– (5 s_a) which quickly returns (7 s_a) to a plain b and is rather maintained as such. The scale seems to be more close to a near perfect G [4424] (with a plain B) d (tonic) 4244424 – or a perfect d mode on d – with a sometimes rather high f (25.*, 26.*, 52.* and 53 s_a), encompassing thus one octave + one fifth. Note also the use (24-25 s_a) of a leading chromatic f# which is particular of the genos mazmūm detailed in the segmentation below.

The “striking pentatonic effect” explained by Snoussi does happen, two times and twice each time, with the omission in descent of the b at 12 and 14, then 40 and 42 s_a (Figure 22)55, and the performance is concluded (64 s_a) on the common tonic d with the next istikhbār by Tarnān.

As a temporary conclusive remark, we can notice some differences in general between theoretical description(s) and practice with Ghānim, with a tendency to use the sub-scales of the tense diatonic division of the octave all along these first 4 istikhbārāt, with slightly moving (otherwise) fixed notes such as the a, the f, etc.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ a-n-Nawā by Muḥammad Ghānim: Detailed segmentation/Analysis

Phrase 1

- 2-9 s_a: genos °ḥsīn° ḥu = a 334 but with a very high b– (practically equal to b).

- 10-15 s_a: genos rāṣd ḥu = a 433 – not really considered as a full genos here, and more characteristic of the nawā (see below) named nafas khumāsī (of pentatonic inspiration) – with high c.

- 16-22 s_a: genos nawā dū = d 4244

- 23-27 s_a: genos mazmūm Rā = C 442 – note the f# at 24.* and 25 s_a

- 28-31.* s_a: repetition of genos mazmūm Rā = C 442

- 31.*-39 s_a: genos nawā dū = d 4244

Phrase 2

- 40-43 s_a: genos rāṣd ḥu = a 433 – not really considered as a full genos here, and more characteristic of the nawā (see below) named nafas khumāsī (of pentatonic inspiration) – with high c.

- 43-49 s_a: genos nawā dū = d 4244

- 50-54 s_a: genos mazmūm Rā = C 442

- 54-56 s_a: repetition of genos mazmūm Rā = C 442

- 56-64 s_a: genos nawā dū = d 4244

Second improvisation by Tarnān by on ʿūd °ʿarbī°: Ṭabʿ al-Iṣbuʿayn

More theoretical differences seem to characterize our two authors for this ṭabʿ. Snoussi56 compares it to the “Oriental” Ḥijāz but with the “Tunisian variant” of the ḥijāz tetrachord, namely d 352, while with Erlanger (Figure 23) the description seems closer to the scale of maqām Shāhnāz in the Near-Eastern tradition. Erlanger’s preference for the pentachordal description is evident in the figure, with two conjunct ḥijāz pentachords, while Snoussi describes the second (disjunct) tetrachord as being composed of “the notes a, b – 1/4 tone, c#, d”, which represents a similar “Tunisian ḥijāz” on a (see Video T.7), a fact which reconciles the two descriptions57 were it not for the pentachordal vs tetrachordal depictions, and for the slight differences in the internal composition of the ḥijāz type.

Finally, Snoussi58 explains that in the ḥijāz tetrachord the central interval (the “5” quarter-tones interval) may furthermore be performed as small as a whole-tone interval, which results (without being named as such by Snoussi) in the ʿirāq tetrachord 343.

As for Tarnān’s performance: the general scale is that of maqām Ḥijāz-Awjī encompassing a (lower) tetrachord (as with Ghānim for Nawā) + one octave from d to D. The ḥijāz tetrachord d 262 does not have a shrunken central interval (i.e. d 352 or even 343) except for rare uses of a slightly raised eb (for example at 75 and 76 s_a). Both theoretical descriptions fail in describing (or prescribing) the upper tetrachord – which is a plain bayāt a 334 – while Tarnān sometimes uses (usual) embellishments (as around 70 and 90.* s_a) incorporating a C# as sub-tonic. Further embellishments – here micro-modulations – are the use of a būsalīk tetrachord in ascent at 105-108 s_a with a plain b, which becomes immediately after (108.* s_a) b– then, in a masterful demonstration by Tarnān of his precision on the ʿūd, the clear use in descent (109.* s_a) of a bb (Figure 24). (Note that b– and B– are frequently slightly high with Tarnān in this mode.)

Finally note that the simultaneous use of multiple – sympathetic, non-stopped – strings by the performer creates local disruptions in the graphic line, notably at 84.* and 87.* s_a.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ al-Iṣbuʿayn (al-°Iṣbuʿīn°) by °Khmayyis° Tarnān. Detailed segmentation/Analysis

- 68-78 s_a: genos °isbuʿīn° d (between 262 and 352) – even if the rukūz/stop is on Rā = C, this is due to the resonance/sounding of the instrument, and because of the placement of the first finger (of the left hand) on the KIRDĀN string in the ʿūd °ʿarbī° to play the d (MUḤAYYAR – see Figure 7)

Ṭabʿ al-°Iṣbuʿīn° d 2624334: The stop (rukūz) on C can hint to a genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° of type 2 4262 on C the use of which is different from its use in other istikhbārāt. But, as long as this is the first genos (and the first phrase) in the istikhbār °Iṣbuʿīn°, it is more likely that this is a genos °iṣbuʿīn° d 262 (or 352) with an accidental stop on the C, probably due to the non-completion of the musical idea (which ends at 105 s_a).

Note the use of a C# from 69 to 71 s_a, which may be used in one of the variants of the °īṣbuʿīn° called inqilāb al °iṣbuʿīn° using a genos °īṣbuʿīn° A (not used in this istikhbār).

- 78-86 s_a: genos °isbuʿīn° d 262 (or 352)

- 86-105 s_a: °Iṣbuʿīn° d 2624334. This part explores the ṭabʿ in the lower register, with micro-stops on d. Note the use anew of C# from 89 to 91 s_a. Also note a micro-stop on C at 96 s_a, delineating a rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° type 2 C 4262. [Note that the °Iṣbuʿīn° of Tarnān is clearly based on a 262 ḥijāz type tetrachord, and rarely on a 352 and not on a 343. This is the reason for this 4262 type 2 rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl°.]

- 105-114 s_a: °Isbuʿīn° d 2624334. Exploration of the ṭabʿ in the higher register, without completely evocating a particular genos, while however rapidly delineating a °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq g (4334) in descent.

- 114-126 s_a: °Isbuʿīn° d 2624334. Development of the ṭabʿ in the higher register (same remarks as above).

- 127-140 s_a: °Iṣbuʿīn° d 2624334. This is a near repetition of 86-105 s_a, with the same melodic path, the same micro-stop on C (at 138-139 s_a).

- 140-151 s_a: 2nd exploration of the higher register of the ṭabʿ without evocation of a particular genos, delineating this time a possible °mḥayyar°-sīkā on g (424) in descent, with a low = bb at 143-144 s_a.

- 151-159 s_a: °Isbuʿīn° d 2624334

- 159-163 s_a: °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq g (4334) – This is the first “clear” usage of a main genos in this istikhbār

- 163-173 s_a: °Isbuʿīn° d 2624334

Analytical conclusion

Unlike with the precedent istikhbārāt, Tarnān develops the °Iṣbuʿīn° “in one piece” with nearly no delineations of genē which could be characteristic of this ṭabʿ. He just passes on the notes of the ṭabʿ while giving hints of a °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq g 433, a °mḥayyar°-sīkā g 424 and the rāṣd a-dh-°dḥil° C 4262 – which is different from the usual 4343 –, the latter probably due to the use of a closer to “262” °iṣbuʿīn° (with a relatively high eb) in place of the “usual” “352” °iṣbuʿīn°.

As a temporary conclusion, and as says the poet: “Not all that Man wishes comes true, The wind blows in directions not desired by the ships”59, or what the theorist prescribes will not be scrupulously reproduced by the performer, who remains the final master of his music, especially when theorists do not even agree among themselves – a frequent case with Arabian-Persian-Turkish music theories.

➤ Analysis 5: The ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° by Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb, then ṭabʿ a-r-Ramal by °Khmayyis° Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 52b)

First improvisation by Ghānim on rabāb: Ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl°

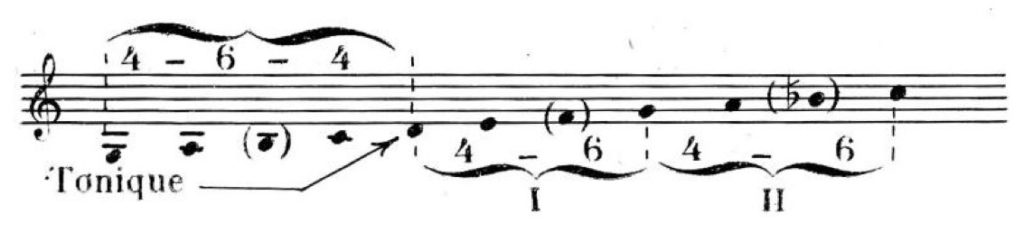

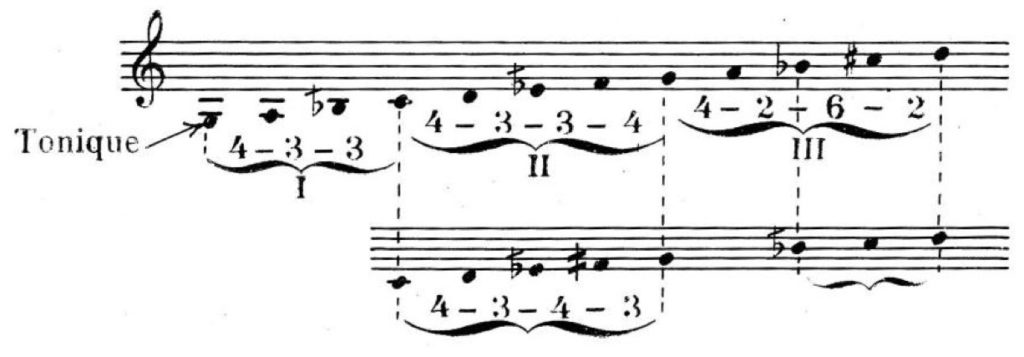

For Snoussi60, the scale of ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° is a simple assembly of two conjunct tetrachords preceded in the lower range, on the tonic c, by a whole tone (Video T.8). The first tetrachord is the “Tunisian ḥijāz”61 in his (Oriental) ʿirāq62 343 version on d, and the second one is a rāst 433 tetrachord on g, with a resulting octaval scale c 4343433 or c d e– f+ g a b– C. This is the same description as with Erlanger in the upper line (Figure 25) with the difference that the notation in Erlanger’s favours the fifth + fourth assembly, as usually seen for other ṭubūʿ with this author.

Erlanger adds (2nd line in the figure) the possibility of including a 352 ḥijāz as an upper component of the lower pentachord (or of using the nakrīz 4352 pentachord on c), a minor modulation which should be permitted – but is not explicitly mentioned – with Snoussi, as he mentions another, “352 Tunisian ḥijāz” (see above). Lastly, Erlanger mentions the possibility (third line in the figure) of a lower rāst pentachord on c.

Figure 25. Ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° as in Erlanger (Erlanger 1949, 5: mode no. II, fig. 149). The intervallic notation in quarter-tone multiples in the upper line was corrected by the authors from 4 – 3 – 5 – 3 to 4 – 3 – 4 – 3.

As for Ghānim’s performance, it would be justified to state that he gives from the onset a pentatonic feeling to this istikhbār with a leap (7.* s_a) from e– to g. While this is followed by a more regular display of the main scale c 4343433, this same leap intervenes at 31 s_a, then back – but descending – at 35 s_a, then again at 57.* s_a and finally once again in descent at 67.* s_a.

Figure 26. A frame from the video analysis of ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° as performed by Ghānim showing one ascending then one descending leaps (31, 35 s_a) from e– to g then from g to e–, giving a distinctive pentatonic aspect to the performance.

While remaining in the range of one octave + one fourth, another peculiarity of his performance is the effective use of both – clearly differentiated – f+ and f in the performance, with one example (around 23 s_a) of such two successive uses, which results in a clear change of the lower pentachord, till 56.* s_a, to a rāst c 4334 pentachord which is the third possibility stated in Erlanger. (See figure above.) However, no clear signs of a c 4352 pentachord or of an upper būsalīk g 424 (see 2nd line in the figure above) are to find in the graphic notation, although the tonic moves nearly continually63 within the limited range of one third-tone64.

Finally, note that Erlanger may here well be right with his pentachordal assembly as the general feeling of this istikhbār is sometimes close to the feeling of a nakrīz pentachord c 4352 (listen to the two octavial scales descents in the first half of the performance, from 16 to 20 s_a and 20 to 27 s_a), would the central “ḥijāz” interval be slightly larger with Ghānim.

To conclude, there are once again some limited affinities between theory and practice, and much to learn from Ghānim’s performances, as limited in time as they may be.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° by Muḥammad Ghānim. Detailed segmentation/Analysis

Phase 1 (7-27 s_a)

- 7-16 s_a: °mḥayyar°-sīkā on na = sol = g 424 (scale)

- 16-20 s_a: descending scale of ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° type 2 (with bb) on c 4343424

- 20-27 s_a: development of the preceding phrase, descending scale of ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl type 2 (with bb) on c 4343424

Phase 2 (28-72 s_a)

- 28-30 s_a: genos sīkā 334 on e– with micro-stop

- 30-38 s_a: development of the scale of ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl type 1 (with b–) on c 4334433

- 38-43 s_a: exploration of the lower register of the ṭabʿ beneath the octave G 433

- 44-50 s_a: continuation in the upper register of the ṭabʿ with a short stop on f. This type of stops doesn’t determine a genos, but may suggest a genos °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq na = g 4334 with a very high aw = b– (nearly a plain b) or possibly a pseudo-mazmūm ja = f 4424 (genos mazmūm uses plain b in the course of the melody). In all cases, this stop on f does not make this genos independent from the rest of the melody.

- 50-56 s_a: ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl type 1 (with b–) on c 4334433. The near-stop on sol = na = g (53 s_a) confirms the intention of a genos °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq na = g 4334 of the preceding phrase.

- 57-72 s_a: development of the scale of ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl type 1 (with b–) on c 4334434 with a very high b– (59 s_a).

Second improvisation by Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī°: Ṭabʿ a-r-Ramal

The scale of ṭabʿ a-r-Ramal is described by Snoussi65 as a maqām Ḥijāz-Awjī disjunct bi-tetrachordal scale d 3524334 with the lower tetrachord corresponding to the “Tunisian variant” of ḥijāz. Let us note from the onset that the demonstration of the scale of this ṭabʿ (analyzed in Video T.9) shows (Figure 27) a plain semi-tonal ḥijāz d 262 which slightly contradicts these explanations. The main characteristic of this mode according to him is the frequent use of the (lower) B– towards the end of the performance, and the obligation to include this note in the final cadenza.

Erlanger (Figure 28) favours a fourth + fifth assembly depicting both scales of maqām Ḥijāz on d, the Ḥijāz-Awjī (through b– = 2624334) and the Ḥijāz-ʿAjamī (through bb = 2624244) scales, with the possibility (second line) of a būsalīk tetrachord on g. Note that the ḥijāz tetrachord proposed with Erlanger is the semi-tonal d 262.

As for the practice: we can notice from the onset in this performance that Tarnān remains generally closer to a “Near-Eastern” ḥijāz d 262 than to a “Tunisian ḥijāz” d 352, with sometimes (around 102.* and 107.* for example) an inversion of the bordering intervals with a d 253 tetrachord. His frequent use of a rather high b– (for example around 120 s_a) then of a low position for this degree (around 131.* s_a) places the main scale of this ṭabʿ somewhere between Ḥijāz-Awjī d 2624334 and Ḥijāz-ʿAjamī d 2624244, with furthermore the 262 ḥijāz tetrachord taking various and all possible variants between 262, 352 and 253, and b– or bb having the possibility of approaching a plain b.

About “the frequent use of the (lower) B– towards the end of the composition”, this is a correct prescription from Snoussi in this case as, after a first occurrence of a call of AWJ (B– at 145.* s_a) followed by a return to the tonic, this call is renewed at 165 s_a, then conclusively at 177.* s_a: note that these “calls of B–“ occur the three times in conjunction with (and just after) a descending ḥijāz d 262 (mostly 253) tetrachord. The use of the latter in this direction partly corresponds to a leitmotiv (Figure 29) clearly discernible between 154 and 156 s_a, with an initial call of fifth d a slightly insisting on the a, followed by a rapid descent omitting the g and slightly insisting on the f#. (The whole process is frequently repeated, for example from 157 to 160 s_a, with a variant for the initial call d a which is a gradual ascension of the degrees of the scale; it is nearly immediately repeated another time between 162 and 165 s_a – Figure 29.)

Note also the use of a ʿirāq d 343 ascending tetrachord around 150 s_a, which adds another “Tunisian ḥijāz” variant for this ṭabʿ, and we have then all the possible forms of ḥijāz, from the “relaxed”, “zalzalian” ʿirāq 343, to the “tense”, “chromatic” 262, and passing through either of the intermediate variants 352 and 253.

Altogether, this and the previous – by Ghānim – performance confirm and complete the theoretical explanations by Snoussi and Erlanger, confirming however and further with Tarnān the use of a multiplicity of ḥijāz variants – already perceived in former analyses of Ḥijāz-like scales66 – whenever the theory prescribes only one (as with Erlanger’s strictly “Near-Eastern” ḥijāz 262) or another (as with Snoussi’s “Tunisian” 352) variant. Furthermore, the descending leitmotiv in Tarnān’s °Ramal° seems to have been missed by Snoussi, but it is maybe a characteristic of the performer’s understanding of this ṭabʿ more than of the ṭabʿ as such67.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ a-r-Ramal by °Khmayyis° Tarnān

Detailed segmentation/Analysis

- 73-96 s_a: exposition of ṭabʿ a-r-Ramal in its most obvious form using a genos °ramal° dū = d 2624, while underlining the typical interval B–_d of the ṭabʿ (94-96 s_a)

- 96-103 s_a: exploration of the upper register of the ṭabʿ with either 262433[4] or 262424[4] with a possible genos °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq na = sol = g 433[4]

- 104-116 s_a: exposition anew of ṭabʿ a-r-Ramal with the same typical B–_d interval

- 17-124 s_a: exploration anew of the upper register of the ṭabʿ with either 2624334 or 2624244

- 125-135 s_a: exploration anew of the upper register of the ṭabʿ concentrating on the degree ḥu = a which suggest a probable genos °ḥsīn° ḥu = a 334

- 135-138 s_a: possible genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā na = sol = g 424

- 138-147 s_a: genos °ramal° d 2624 with the same typical B–_d interval

- 147-153.* s_a: genos °ramal° d 3434 (Let us here note that Tarnān has deliberately reduced the extent of the eb_f# interval)

- 153.*-166 s_a: genos °ramal° d 2624 with the same typical B–_d interval

- 166-180 s_a: exploration anew of the upper register of the ṭabʿ with either 2624334 or 2624244

Analytical conclusions

Tarnān’s performance testifies for a jerky/abrupt interpretation with micro-stops on nearly all the degrees of the ṭabʿ a-r-Ramal, with a repetition of a descending melodic formula – which could well be the “signature” of the ṭabʿ – all along the sayr al-ʿamal, using the notes a f# eb d B– d.

Although no clear stops are used to underline particular genē, two can be detected, namely a °mḥayyar°-ʿirāq na = sol = g 4334 and a °mḥayyar°-sīkā na = sol = g 4244.

Video 5: Video analysis of the istikhbār in ṭabʿ Rāṣd a-dh-°Dhīl° by Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb and the istikhbār in ṭabʿ a-r-Ramal by °Khmayyis° Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī°

➤ Analysis 6: The ṭabʿ al-Iṣbahān by Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb, then ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm by °Khmayyis° Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 53a)

In these two istikhbārāt we will note the very rich performance by Ghānim, with many modulations, and the consistent differences between prescriptive theory and effective practice.

First improvisation by Ghānim on rabāb: Ṭabʿ al-Iṣbahān

For the ṭabʿ al-Iṣbahān the differences between Snoussi68 and Erlanger (Figure 30) are even more accented as for the preceding ṭubūʿ. For Snoussi (Video T.10) the tonic of the mode Iṣbahān corresponds to the lower g, as with Erlanger, and the first tetrachord (rāst 433 on g) is the same for both. However, Snoussi (as usual) favours a purely tetrachordal assembly of the octave, with here a disjunctive tone between c and d, with an upper similar rāst tetrachord 433 on d, which corresponds to the final scale g 4334433 equivalent to the scale of maqām Rāst (traditionally on c but here) on g.

This second tetrachord is absent from Erlanger’s notation, who proposes a rāst pentachord on c resulting in the scale g 4334334, different from Snoussi’s proposed scale. Erlanger proposes (2nd line) also a 4343 “extended ʿirāq” pentachord69 on g as an alternative to the rāst 4334 pentachord on c, resulting in the scale g 4334343, with both scales bearing an upper extension on (upper) G consisting in a semi-tonal nakrīz type pentachord 4262, an extension which is missing in Snoussi’s explanations. The latter favours, furthermore, a descending būsalīk 424 tetrachord on c in place of the rāst tetrachord, which completes the series of dissimilarities between the two descriptions.

Let us note, finally, that this author mentions “frequent falls70 [‘omissions’?] of one degree in the descending movement [of the melody]”, that we find in the performance of Ghānim solely as (initial, then repeated, frequent) calls of fourth from d to the upper octave G (see 2.*, 3.*, 8, 8.* etc. s_a), with further omissions of the f in descent (for example at 58.* s_a).

Lastly, let us point out that Erlanger’s comprehension (Figure 30) supposes a possible sīkā (or oriental ʿirāq) 34 trichord on the upper B–.

The main scales used by Ghānim, in the range of one octave + one fourth, are the fully zalzalian g 4334334 (the main scale with Erlanger) and the semi-zalzalian g 4424334 – with a būsalīk 424 on a – with frequent changes between b (B) and b– (B–). Two main modulations can be noted in his performance: a modulation from 31 to 35 s_a to a genos ḥijāz d 352 (“Tunisian ḥijāz” according to Snoussi in preceding explanations about other ṭubūʿ 71) then going through an instant rāst like type tetrachord d 433 returning to the semi-zalzalian version g 4424334 beginning with 39 s_a. Then, at 48 s_a, Ghānim starts after a very short pause from the upper D descending in what seems well to be a nakrīz like (but with a – sharqī, “oriental” – ʿirāq 34372 on A instead of a semi-tonal ḥijāz 262 on A – see Figure 31) pentachord on G then, after a double call of fourth d-G-d (around 55 s_a) returns (55.* s_a) to the semi-zalzalian scale g 4424334 G [4424] but with a clear alternation of lower b and b– (63 to 66 s_a) with a final end on the tonic g.

As a conclusion: except for the tonic g for both authors (Snoussi and Erlanger), and despite the consistent differences between the two, their two descriptions brought together fail at describing the richness of Ghānim’s performance, which he completes within less than 70 seconds for the complete istikhbār.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ al-Iṣbahān by Muḥammad Ghānim. Detailed segmentation/Analysis

- 2-11 s_a: genos rāṣd on d = ré 4(2)44

- 12-21 s_a: genos iṣbahān on g = sol = YĀKĀ 4334; note a very high b– practically equal to b, and a slightly high a

- 22-30 s_a: genos iṣbahān on g = sol = YĀKĀ 4334

- 30-35 s_a: genos °iṣbuʿīn° on d = ré = DŪKĀ 3524

- 35-47 s_a: genos iṣbahān on g = sol = YĀKĀ 4334

- 48-54 s_a: genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° type 2 on G = Na 4343

- 54-59 s_a: genos rāṣd on d = ré 4(2)44

- 59-68 s-a: genos iṣbahān on g = sol = YĀKĀ 4334

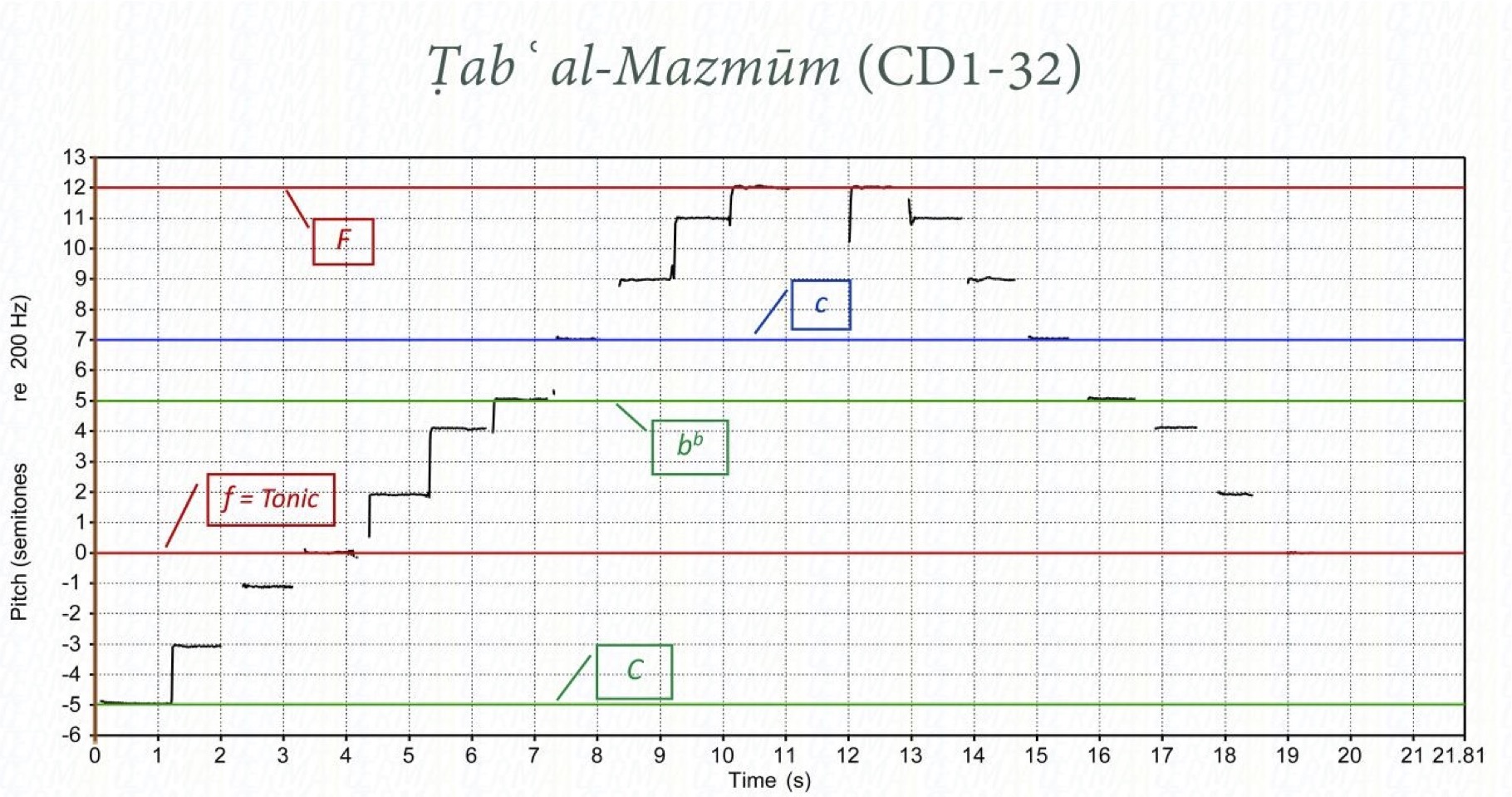

Second improvisation by Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī°: Ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm

For Snoussi73, the main scale of ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm on tonic f results from a two tetrachord disjunctive scheme (tetrachord + whole-tone + tetrachord) with two jahārkā 424 (also called ʿajam in the Near-Eastern tradition) tetrachords on JAHĀRKĀ (f) and on c with the intervallic ascending composition 4424442 (Video T.11). It is completed, as with Erlanger (Figure 33), by a lower rāst 433 tetrachord on (lower) C – but the analysis of the audio scale provided in Snoussi’s CD1 shows otherwise (see Figure 32). The cadenza finishes necessarily, for Snoussi, on the tonic f while Erlanger proposes further a variant with a bayāt tetrachord on a, which gives the alternate – and non-octavial – scales [433] f 44244 (ʿAjamī) and [433] f 44334 (Awjī).

Tarnān’s performance, on the other hand, is rather straightforward, encompassing a wide two-octaves range (Figure 34), with sometimes low (middle) fs and gs and high e–s, with a dynamic strike and rather intermittent pitches showing micro-modulations (such as at 146 s_a with alternating plain cs with a low c, or around 168 s_a with alternating near-exact and rather low b–s – Figure 34). The final cadenza (178-181 s_a – Figure 34) plays mostly on the open strings C and G, with a pentatonic feel (with B– omitted in descent then in ascent around 179.* s_a).

Tarnān’s straightforward performance (scale wise) of this ṭabʿ as a zalzalian mode of f on f, and his cadenza on the lower octave of the mode show once again, if any such demonstration is still needed, the consistent differences between performance practice and theoretical speculations by both Snoussi and Erlanger.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm by °Khmayyis° Tarnān

Detailed segmentation/Analysis

- 71-78 s_a: genos mazmūm on f = fa = ja 4433. Note the use of a low E practically equal to E–

- 79-94 s_a: development of genos mazmūm on f = fa = ja 4433. Note the use of a high bb = sib practically equal to b– except at 89 s_a where a clear bb can be found; note also the use of a slightly low E close to E–

- 95-102 s_a: genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° type 1 on C = Do = Rā 4334. Genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° type 1 on C is not frequent with ṭabʿ al-mazmūm f. Maybe the intent was of a mazmūm on C 4424, the E = Mi remains however low, equivalent to E–.

- 102-114 s_a: development of mazmūm on f = fa = ja 4433. Tarnān does not use a bb! But the E tends to become closer to its theoretical pitch value (= E)

- 114-120 s_a: typical stop of ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm on the degree a, with “usually” a kurd genos a 244; However, Tarnān uses here a high b = b– which transforms the kurd genos into a genos °ḥsīn° a 334, which is not of current use in today’s Mazmūm

- 121-132.* s_a: development of mazmūm on f = fa = ja 4424. This development seems to come closer to the current common understanding of ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm, including among others the concentration on the degree a, and the alternation between the degrees b (at 121-122 s_a, but beware that it is mostly – at 123.*, 125.* and 126.* etc. – a b– with Tarnān) and bb

- 132.*-138 s_a: could have been a sub-tonic genos mazmūm on C 443. While the E is higher, but still relatively low (close to E–), this is in favour of genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° type 1 on C = Do = Rā 433.

- 138-154 s_a: genos mazmūm on f = fa = ja 4433

- 154-172 s_a: development of genos mazmūm on f = fa = ja 4433. The E (for example at 156 s_a) is clearly close to its nominal pitch, and even higher during the exploration of the utmost high register of the ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm (for example at 164 s_a), while the supposed bb remains closer to b–.

- 172-178 s_a: genos mazmūm on f = fa = ja 4433

- 178-181 s_a: genos mazmūm on F = Fa = Ja 4433 completing the extensive range of the ʿṭabʿ (2 octaves).

Analytical Conclusion

Ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm is today taught as having a structural scale f 4424442 with a genos mazmūm on JAHĀRKĀ = f 4424, a genos of the kurd type 244 on ḤUSAYNĪ = a, a genos mazmūm on KIRDĀN = c 4424 and a genos mazmūm on RĀST = C 442 under the tonic f. The mazmūm genos on f has frequently a plain b as inlay (embroidery). However, with °Khmayyis° Tarnān, the structuring scale of ṭabʿ al-Mazmūm seems to be an f 4433433, rarely using a bb and with low e and E nearly for the whole development of the ṭabʿ. Genos 4433 is not “officially” recognized in Tunisian music today, even though it is used and valued in different ṭubūʿ improvisations. If its use by Tarnān as an independent genos is confirmed – with an infrequent bb used for “embroidery” – this could bring changes to the theory of this ṭabʿ and, consequently, in its interpretation.

➤ Analysis 7: The ṭabʿ al-Māyā by Muḥammad Ghānim on rabāb, then ṭabʿ al-°Mḥayyar°-Sīkā by °Khmayyis° Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī° (CDC HC 53b)

Two istikhbārāt in which we find the conclusive indications about the consistent differences between theory and practice.

First improvisation by Ghānim on rabāb: Ṭabʿ al-Māyā

For Snoussi74, the tonic of ṭabʿ al-Māyā is c, whenever with Erlanger it is the e– above it (Figure 35). While the scale with both theoreticians is more or less similar, it is as ever with Snoussi delineated by two tetrachords75, conjunct in this case with an upper tone complementing the octave. The lower tetrachord is of the rāst type 433 on c, while the second (upper) tetrachord is of the type jahārkā 442 on f, which gives, with the tone bb_C, the semi-zalzalian scale c 4334424. (Video T.12)

Were it not for the difference with the tonic, this would correspond to the main scale with Erlanger, who complements it still with the two lower B– and A notes, and proposes a variant using a nahawand (or būsalīk) 424 upper tetrachord on g.

In Ghānim’s performance of the istikhbār in this ṭabʿ, the tonic is clearly enunciated at the beginning (2 s_a), the end (66-68 s_a and Figure 36) and in the meantime (14, 16.*, 39, 45, 46, 56.*, 59, 63 and 64 s_a), as well as the (upper) octave (9.*, 17.*-19.*, 24-25, 29.*, 31.*, 34.*, etc. s_a). It is the c for a regular Zalzalian c (Rāst) scale 4334433, developed from the lower fourth degree (G) to the (upper) octave (C). It is only towards the end that we can sense a definite modulation to a genos nakrīz c 4352 (60-68 s_a and Figure 36), and a repeated portamento-like descending upper pitch from g to f# (59.* 61.*) with an interspersed (61 s_a) call of e–. In the regular main Zalzalian scale, the b– never reaches in a stable manner bb or b plain, a clear difference with the ʿajam 442 or the būsalīk 424 advocated in Erlanger. Furthermore, none of the theoreticians anticipates the nakrīz 4352 on c which is a major modulation with this performer.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ al-Māyā by Muḥammad Ghānim. Detailed segmentation/Analysis

- 2-5 s_a: genos sīkā [43] e– 3(44). (The micro stop on d is not structural).

- 6-17 s_a: Exposition / exploration of the scale of ṭabʿ al-Māyā [33] c 4334424. Note that the B– and the A (below the tonic c) are very high.

- 17-27 s_a: genos mazmūm f 4424 or 4433, with a varying degree b (low at 20 s_a, and high at 20-23 s_a,and mostly for the cadential phrase of the genos around 25 s_a)

- 28-39 s_a: genos māyā c 4334 while delineating the whole scale of the ṭabʿ

- 40- 45 s_a: development of genos māyā c 4334

- 45-48 s_a: genos sīkā [43] e– 3(44). (the same suggestion proposed at the very beginning of the istikhbār – see 2-5 s_a)

- 48-59 s_a: Exposition / exploration of the scale ṭabʿ al-Māyā [33] c 4334424. Note that the b– and the A (below the tonic c) are very high.

- 59-68 s_a: genos rāṣd a-dh-°dhīl° type 2 on c 4352 with the cadential formula of ṭabʿ al-Māyā at 64-68 s_a

The gap between theory and practice is further widened in the istikhbār in ṭabʿ al-°Mḥayyar°-Sīka by Tarnān.

Second improvisation by Tarnān on ʿūd °ʿarbī°: Ṭabʿ al-°Mḥayyar°-Sīkā

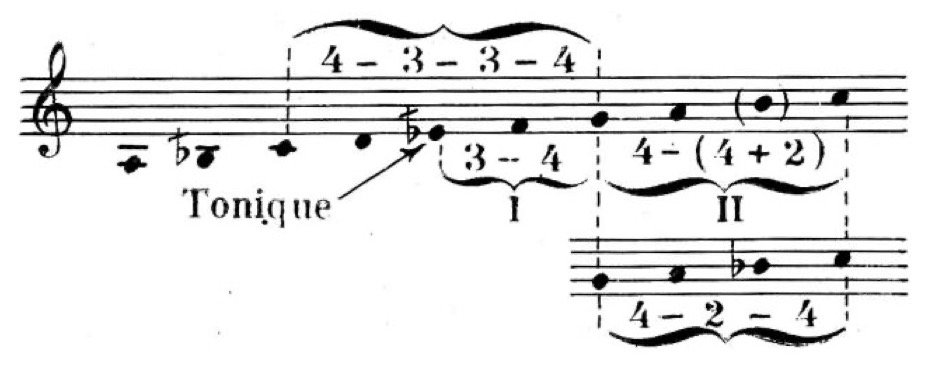

Once again we have a difference from the onset between Snoussi (Video T.13) and Erlanger (Figure 37) for the scale of this ṭabʿ, as it is given as d by the first while it is g with the second. Moreover, the first tetrachord on d with Snoussi is of the būsalīk type 424 while it corresponds to a lower addition for Erlanger, of the ḥijāz 262 type. Comes then a disjunctive tone g_a for Snoussi whenever Erlanger favours – as usual – a pentachordal/tetrachordal construct, here with a būsalīk pentachord 4244 on g, while Snoussi writes that it is a kurd tetrachord 244 on a.

Erlanger insists on using a further upper ḥijāz 262 tetrachord on (upper) d (or D, depending on the tonic) while Snoussi explains that this tetrachord can be performed alternatively on a (in place of the kurd tetrachord) and warns that while the range of the ṭabʿ is, “in principle”, one octave (from d to D), it does not, however, in practice, reach this limit and stops generally at bb. Finally, let us note that Erlanger introduces another ḥijāz pentachord 2624 on c in the upper range (where Snoussi says that the ṭabʿ does not extend), and with this we have a last consequent difference between the two theoretical descriptions of the scale of this mode.

We can conclude from Tarnān’s istikhbār in this ṭabʿ that the tonic is undoubtedly d, with a development the range of which is a double-octave from (upper or lower) D to (lower or upper) D (Figure 38). These are already two major difference with Erlanger (the tonic) and with Snoussi (the range of the ṭabʿ), as if Tarnān wanted expressly to differentiate himself from both theories. Furthermore, the main scale of this ṭabʿ is a Zalzalian d mode of the Bayāt or Ḥusaynī type. A major modulation does occur, and to a ḥijāz type genos (149-155.* s_a) but it is positioned neither on d or even on c or (upper) D as favoured in Erlanger, but on a (Figure 38). Note also the use anew in this istikhbār of a clear leitmotiv, prepared at first from 86.* to 94.*, then enunciated twice from 95 to 96.* then at 97-98 s_a, and repeated or hinted a few more times at 116-118, 125.*-127, 127-128.*, etc. s_a.

Modern Tunisian Analysis of the sayr al-ʿamal of ṭabʿ al-°Mḥayyar°-Sīkā by °Khmayyis° Tarnān

Detailed segmentation/Analysis

- 73-86 s_a: genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā on d = ré = dū 4244. Note that the second and the third degrees (e and f) are slightly low.

- 86-95 s_a: genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā on d = ré = dū 4244 with the exploration of the scale 4244244 of the ṭabʿ. Let us note that the second and the sixth degrees (e and b) are consistently lower than their today’s use in the interpretation of the °Mḥayyar°-Sīkā. This is equivalent to a scale d 3344334 corresponding to ṭabʿ °Ḥsīn°.

- 95-109 s_a: genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā on d = ré = dū 4244. Tarnān uses two important specificities of the ṭabʿ: the suite a f e d (la fa mi ré) while omitting the note g (sol) at 95-98 s_a, and the use of ab which may be considered as a form of taṭrīz (“embroidery”) for this ṭabʿ, but also maybe as a suggestion of a genos °iṣbuʿīn° g 262, another possibility for modulation in this ṭabʿ. Moreover, it must be noted that the second and third degree of the ṭabʿ, namely the e and the f, are clearly lower than in today’s practice, delineating the scale as d 3254244

- 109-119 s_a: genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā on d = ré = dū 4244. Here the sixth degree becomes bb, and the third degree f is no more low. In contradistinction, the second degree remains relatively stable as e–

- 119-125 s_a: genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā on d = ré = dū with a scalar descent d 32542.

- 125-140 s_a: same analysis as for 95-109 s_a (i.e. genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā on d = ré = dū 4244 with a scalar descent d 32542)

- 141-149 s_a: exploration of the ṭabʿ in the lower octave. Note the clear use of Bb but also of a low E– which reminds of the cadenza of maqām Bayāt D 3344244

- 149-155 s_a: genos °iṣbuʿīn° a = la = ḥu 262 or 253

- 155-160 s_a: genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā on d = ré = dū 3254.

- 160-167 s_a: genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā on d = ré = dū 4244 with a scalar descent d 32542.

- 167-182 s_a: same analysis as for 95-109 s_a (i.e. genos °mḥayyar°-sīkā on d = ré = dū 4244 with a scalar descent d 32542). Note that the taṭrīz here reminds of a pseudo °iṣbuʿīn° g = sol = na 253, which is one possible additional genos for the use in ṭabʿ °Mḥayyar°-Sīkā

Analytical conclusion

In the tradition of Tunisian °Mālūf° (for Maʾlūf), the °Mḥayyar°-Sīkā (pretty much as the °Mḥayyar°-ʿIrāq) is a popular ṭabʿ. It is not associated with a particular °nūbā° and it is mainly used as a genos in different other ṭubūʿ.

Today, the ṭabʿ °Mḥayyar°-Sīkā has one only scalar composition, d 4244244. As noted above, the actual composition of this ṭabʿ with Tarnān is 3254244, resulting from the consistent lowering of the second and third degrees of the scale.

In the course of this performer’s interpretation, notably for 91-94 s_a and 141-149 s_a, Tarnān disconnects somehow from the usual context of the °Mḥayyar°-Sīkā creating first a confusion with the °Ḥsīn° (with a 3444344 scalar composition), then through a transformation of his modal language towards a Bayāt. This evolution is incomprehensible as is, and gives way to many exegeses which will be necessarily relied to parameters which will be external to music – this would, however, be in itself the subject of another article.

Conclusions about the analyses of the Tunisian ṭubūʿ

It is evident that a great number of analyses must be undertaken before any consensus may be adopted on the description of each ṭabʿ, even for the simplest of descriptors which is the scale(s). Moreover, significant differences were found between the practice of both Muḥammad Ghānim and °Khmayyis° Tarnān (but more for the latter) and the practice today of the ṭubūʿ: this is true in particular for Ghānim’s performance of ṭabʿ a-r-Rahāwī, the whole ṭabʿ having went “out of fashion” today as it is seldom used in Tunisian Maʾlūf. This is also true for example with ṭabʿ °Raml° al-Māyā as performed by Tarnān (Analysis and Video 3, second part), for which considerable discrepancies with today’s description of the ṭabʿ are perceptible.

When noting, in parallel and as explained by Moussali in the above quotes, that the two musicians were asked to “recreate” an already nearly lost tradition at that time76, it has thus become clear that only part of the Tunisian tradition was transmitted from the past, and that a thorough analysis of the Early recorded repertoire should be undertaken to try and recover other bits of the lost tradition of the Tunisian ṭubūʿ, and to determine which other parts are effectively “Tunisian”, and which others may have been “re-created” through the aforementioned process, either at the beginning of the preceding century, or since then…

We can only hope that our very modest attempt at reviewing and analysing a small part of the Tunisian repertoire will be the catalyser for other, wider research on these and other musics, in the hope these would regain their status of living musics, and not of mummified remains of the past.

Bibliography/Discography

- Beyhom, Amine. 2003. “Systématique modale – En 3 volumes.” PhD Thesis, Université Paris Sorbonne. [Sudoc], [Publications of Amine Beyhom].

- ———. 2005. “Approche Systématique de La Musique Arabe : Genres et Degrés Système.” In De La Théorie à l’Art de l’improvisation : Analyse de Performances et Modélisation Musicale, edited by Mondher Ayari, 65–114. Paris: Delatour. [read the online].

- ———. 2016. “Dossier: Hellenism as an Analytical Tool for Occicentrism (in Musicology) (V2).” Near Eastern Musicology Online 3 (5): 53–275. [read online].

- ———. 2017. “A Hypothesis for the Elaboration of Heptatonic Scales.” Near Eastern Musicology Online 4 (6): 5–89. [read online].

- ———. 2018. “MAT for the VIAMAP. Maqām Analysis Tools for the Video-Animated Music Analysis Project.” Near Eastern Musicology Online 4 (7): 145–258. [URL: http://nemo-online.org/].

- ———. 2019. “The Lost Art of Maqām – With Four Video Analyses of Performances by Evelyne Daoud, Neyzen Tewfik, Hamdi Makhlouf, and by ʿAlī Maḥmūd and Sāmī a-Sh-Shawwā.” Near Eastern Musicology Online 5 (8): 5–64. [read online].

- ———. 2021. “Further Analyses from the VIAMAP.” Near Eastern Musicology Online 6 (10): 5–36. [URL: http://nemo-online.org/archives/1925].

- Erlanger, Rodolphe (d’). 1949. La Musique Arabe (5) – Essai de Codification Des Règles Usuelles de La Musique Arabe Moderne. Échelle Générale Des Sons, Système Modal. Vol. 5. 6 vols. Paris, France: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner.

- Guettat, Mahmoud. 1980. La Musique Classique Du Maghreb. La Bibliothèque Arabe. Collection Hommes et Sociétés, ISSN 0990-4913 ; 5. Paris, France: Sindbad.

- Mahdī (al-), Ṣalāḥ. 1972. La musique arabe: structures, historique, organologie. Paris: Alphonse Leduc.

- ———. n.d. La Nawbah Dans Le Maghreb Arabe: Nawbet Adhil Tunisienne. Patrimoine Musical Tunisien. Tunis: Conservatoire National de Musique et de Danse.